Do the scientific community and society agree

on the use of Artificial Intelligence in education?

¿Coinciden la comunidad científica y la

sociedad sobre el uso de la Inteligencia Artificial en educación?

Dra. Sonia

Martín-Gómez. Profesora adjunta. Universidad San Pablo

CEU. Madrid. España

Dra. Sonia

Martín-Gómez. Profesora adjunta. Universidad San Pablo

CEU. Madrid. España

Dr. Ángel Bartolomé

Muñoz de Luna. Profesor Titular. Vicerrector de Estudiantes

y Vida Universitaria. Universidad San Pablo CEU. Madrid. España

Dr. Ángel Bartolomé

Muñoz de Luna. Profesor Titular. Vicerrector de Estudiantes

y Vida Universitaria. Universidad San Pablo CEU. Madrid. España

Received: 2024/06/04 Reviewed 2024/07/28 Accepted: :2024/12/10 Online First: 2024/12/18 Published: 2025/01/07

Cómo citar este artículo:

Martín-Gómez,

S., & Muñoz de Luna, Ángel B. (2025). ¿Coinciden la comunidad científica y

la sociedad sobre el uso de la Inteligencia Artificial en educación? [Do the scientific

community and society agree on the use of Artificial Intelligence in

education?]. Pixel-Bit. Revista De Medios Y Educación, 72, 139–157. https://doi.org/10.12795/pixelbit.107530

The main objective

of this research is to explore and understand the development and

implementation of AI in the context of higher education at a scientific and

social level, using a systematic methodology of reviewing scientific papers

from the Web Of Science (WOS) database for the

scientific part and a social listening analysis for the social field. The

bibliometric study, through the Rstudio Cloud

application, allows us to extract a meta-analysis on the topic of IA in higher

education, from 2019 to the present, achieving an evaluation of 32 articles

according to the guidelines of the PRISMA declaration.

For its part, the Brandwatch platform allows us to find out what is being

said online about the use of AI in higher education, studying a total of 27,735

mentions, only from the last year.

By comparing the

scientific and social results, conclusions are drawn on the current challenges

of AI in universities, highlighting the need for researchers to start analysing the impact of the good use of AI tools as a

teaching methodology, so that society can also highlight it in its mentions on

the networks.

El objetivo principal de esta

investigación es explorar y comprender el desarrollo y la implementación de la Inteligencia

Artificial (IA) en el contexto de la educación universitaria a nivel científico

y a nivel social. Se va a usar una metodología sistemática de revisión de

documentos científicos a partir de la base de datos Web Of Science (WOS), para

la parte científica y un análisis de social listening para el ámbito social. El

estudio bibliométrico, a través de la aplicación Rstudio Cloud, permite extraer

un metaanálisis sobre el topic IA en educación superior, desde el año 2019

hasta la actualidad, consiguiendo, según directrices de la declaración PRISMA,

una valoración de 32 artículos.

Por su parte, la plataforma

Brandwatch permite conocer lo que se habla en la red sobre el uso de IA en la

educación superior, estudiando un total de 27.735 menciones, solo del último

año. Comparando los resultados científicos y sociales, se alcanzan conclusiones

sobre los desafíos actuales de la IA en la universidad, destacando que es

necesario que los investigadores empiecen a analizar los efectos del buen uso

de las herramientas de la IA como metodología docente, de forma que la sociedad

pueda destacarlo también en sus menciones en redes.

KEYWORDS · PALABRAS CLAVES

Artificial intelligence; higher education;

scientometrics; mentions; social listening

Inteligencia artificial;

educación superior; cienciometría; menciones; escucha social

1. Introduction

The use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) has been increasing

in recent years, making a name for itself in various fields such as medicine,

finance, law, law enforcement, business, and industry and entertainment

(Salas-Pilco & Yang, 2022); therefore, the IoT (Internet of Things) is a

thing or a collective network of connected devices that facilitate

communication between connected devices, devices and the cloud, as well as

between the devices themselves) will continue to grow in the coming years to

reach 66 billion units in 2026, with 87% of the total number of units in the

next few years to reach 66 billion units in 2026. Users state that, once they

have tried such devices, they will no longer give up their benefits, according

to the second edition of the Things Matter 2019 Report, produced by Telefónica.

The technological evolution of the last few years has

had a positive and/or negative impact on societies around the world so that

people's modus vivendi are affected. Health, the economy, and, obviously, in

education and training (Alonso-de-Castro & García-Peñalvo, 2022). This means that AI has become a synonym for

new promises, but it is also necessary to take into account the risks that come

with the massification of digital technologies in the different spheres of

economic and social life and social problems of the 21st century, as there is a

perception that it will put jobs at risk of those who do not adapt to this new

technological revolution.

Many studies attempt to gauge the pace and depth of

the changes that are taking place as many industries are automating processes

thanks to new technologies and new innovations. Machines are available and

prototypes of inventions are tested that until recently seemed to be science

fiction (Kaku, 2012). In the face of all these developments, we wonder how AI

will impact education, which is considered a fundamental pillar for society's

progress and individuals' development. In an increasingly digitised and globalised

world, AI has become an increasingly important tool and essential tool for

enhancing and personalising the educational experience, understanding the

ability of machines to learn, reason, and autonomously make decisions, and its

application in education is constantly growing and adapting(Halili, 2019).

Artificial intelligence (AI) is playing an

increasingly important role in the field and the educational environment is

affected by all the changes it generates, ranging from preschool stages to

higher or post-graduate levels (Moreno & Pedreño, 2020), as their

application has the potential to transform how we teach and learn.

Here are some of the ways in which AI is being used in

education:

1. Personalisation of

learning. AI can adapt the content and pace of learning to each learner's

individual needs. This means that students can receive specific instruction and

exercises according to their level of proficiency, learning ability, and

learning style, which can increase the effectiveness of learning.

2. Virtual tutoring. AI

systems can act as virtual tutors, providing instant feedback to students as

they work on problems or tasks. This can help learners to understand the

concepts and correct errors better immediately.

3. Data collection and

analysis. AI can collect and analyse large amounts of data on student

performance. Educators can use this information to identify areas for

improvement, to identify trends in learning and to make informed decisions

about teaching.

4. Automation of

administrative tasks. AI helps automate tasks administrative tasks, such as

grade management, class scheduling, and communication with students and

parents. This allows educators to focus more on individualised teaching and

support.

5. Adaptive learning. AI

systems help to adjust the content and the learning activities according to the

progress of each student. This can ensure that students are constantly

challenged and engaged.

6. Evaluation of

open-ended responses. AI allows for the evaluation of open-ended responses,

such as tests and answers to developmental questions, using algorithms of

natural language processing. This can save educators time in correction and

provide more objective feedback.

7. Access to online

educational resources.AI helps students find online learning resources that are

tailored to their specific needs, recommending relevant courses, tutorials and

study material.

In conclusion, we can affirm that specifically in

education, the artificial intelligence education refers to its use in support

of feedback and guidance and automated systems in the field of education (Song

& Wang (2020). In this scenario, the teacher has to be the protagonist in

the classroom, analysing the information provided by the AI, and guiding and

articulating the work of the students. The challenge relates more to the

capacities of teachers to carry out these tasks, as relatively few have the

necessary skills to perform these tasks to process the sheer volume of

individual information that the new systems provide, and/or to translate it

into the personalised responses they are supposed to provide (Lu& Harris,

2018).

In addition, it is important to remember that the

successful implementation of AI in education also raises challenges and ethical

issues. These include concerns about the privacy of student data, equity in

access to technology, and the need to maintain a balance between automation and

human interaction in the educational process. AI in education is a powerful

tool, but its use needs to be carefully considered and monitored to ensure that

it benefits all stakeholders and students fairly and effectively.

Based on the above, this study aims, on the one hand,

to conduct an empirical analysis of the evidence found within the scientific

literature on the use of AI in education and, on the other hand, a social

listening analysis for the use of AI in education to see whether scientists and

society are moving in the same direction. There are some previous systematic

reviews on AI in education (Martinez-Comesaña et al., 2023; Jimbo-Santana et

al., 2023; Fajardo Aguilar, 2023), although they are very limited in comparison

to AI research, but there are no studies that have been conducted that compare

the opinion that emerges from (scientific) systematic reviews with the social

listening (society).

For Zawacki-Richter et al (2019) there is a lack of critical

reflection on the challenges and risks of AI in education in the majority of

scientific articles and a weak connection between AI and education with

theoretical pedagogical perspectives, so the need arises to follow up on the

exploring ethical and educational approaches in the application of their use in

higher education; Along the same lines, Hinojo-Lucena et al. (2019), after

carrying out a bibliometric study stressed that more empirical, research-based

results are needed in order to understand the potential of AI in higher

education.

In summary, this study attempts to address the

following research questions:

·

How do you approach the use of artificial intelligence

for university education?

·

Do scientists and society agree in their assessments

and has there been the same growth as in the past in both communities?

2. Methodology

For scientometrics or bibliometrics, this study follows the

guidelines of the Declaration of the European Parliament and the Council of

Europe, PRISMA, which consists of the use of search engines to search for

indexed articles in order to obtain the necessary

information required on studies that have already been carried out (Barquero

Morales, 2022; Page et al., 2021). The five-step framework of Arksey and

O'Malley (2005) for mapping the scientific literature,

consists of: a) identification of the research question; b) systematised

search for scientific evidence; c) selection of the most appropriate (d) data

extraction; and (e) data collection, summarisation

and dissemination of results.

The

study focuses on the scientific articles published in the Wos database in the

period 2019 to 2023, which have been processed using the Bibliometrix

application for R Studio Cloud, which allows a complete bibliometric analysis

to be performed, following the flow of scientific mapping work (Aria &

Cuccurullo, 2017). The articles obtained were selected based on a Boolean

search generalist "Artificial Intelligence AND university studies",

following these criteria of exclusion:

·

Type of document: article.

·

Years

of publication: between 2019 and 2023.

·

Language: English and Spanish

·

Category

of Wos: Education &Educational Research.

·

Web of Science Index: ESCI, SSCI and

ESCI-Expanded.

With

these restrictions, a total of 36 articles were obtained, which after reading

and the number of projects evaluated following PRISMA has been reduced to 32,

either because they are repeated or because their field of research is not

directly related to education.

For

research based on social listening, the methodology is used as a means of to

understand users' perceptions of a given topic or issue (Herrera et al., 2022),

as it works not only with one's own perception but also with any other

perception (Herrera et al., 2022) anchor point to be established between the

user and the subject under study, based on primarily in the use of technology

and algorithms that track and compile automatically gather data from various

online sources: social networks, blogs, forums, news, etc. and other types of

websites. Once the data is collected, it is then analysed

in order to identify patterns, tendencies and

feelings, applying techniques such as processing natural language (NLP) and

text analysis (Cambria, 2016).

In

general, the social media analysis process is usually divided into four phases:

(Stieglitz et al. 2018):

·

Discovery:

identification of content and corresponding keywords,

·

Hashtags,

etc. that will contribute to the definition of the objectives of the analysis

and the main hypotheses to be tested.

·

Monitoring:

identification of data sources and data collection.

·

Preparation:

preparing the data for further analysis.

·

Analysis:

application of various analysis methods and techniques to the data set prepared

to answer the questions posed in the discovery phase.

In

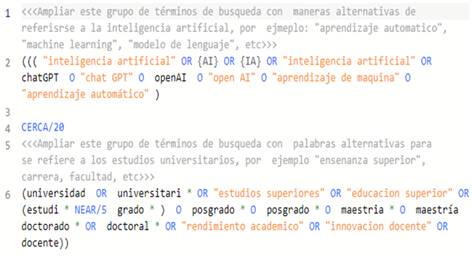

this research, as shown in Figure 1, the same steps will be followed as

proposed by Stieglitz, adding one more, which refers to the implementation of

the need for effective communication of the results of the project, including

the need of social network analysis, as proposed by

the Brandwatch software, which is the platform used

to carry out this social listening.

Figure 1

Mapping Brandwatch

core functions to the network analysis process framework

Brandwatch Search, a search engine, is used for the discovery

stage based on artificial intelligence, which uses sophisticated computer

processing techniques to process natural language. In this case, the search is

linked to the use of social networks in research. In the follow-up phase, the

so-called Query is formed which refers to the set of words used to retrieve

information from the platform's systems. For this purpose, Barean

operators have been used to combine the concepts and refine the results to be

achieved, as shown below:

This

query returns 2,150 mentions on the day of the survey alone in the last 30

days, having filtered by language (Spanish) but searching in anywhere in the

world. Therefore, tools are needed to segment and filter this information,

among others, a test preview to instantly assess the kind of mentions that are

retrieved from the current consultation logic, favouring

the intended social analysis; in this search, it has been decided to remove

websites that mentioned the terms consulted, but are not related to the

objective of the study.

Finally,

the query is maintained, filtered by language, invalid sites are eliminated and

a date range of one year is used to analyse whether

the evolution of the content object of study follows a certain pattern.

In

the last two stages, the results are analysed and

implemented through the use of so-called dashboards

which monitor and examine visually the key indicators.

For

this network analysis, a sampling rate of 100 % is used with sampling rates of

estimated mentions of 1,995 per month.

3. Analysis and

results

3.1. Statistical results of Bibliometrix for R Studio Cloud

Following the bibliometric study carried out with the

R Studio Cloud programme, we proceed to analyse the results obtained at the

scientific level in order to be able to respond to the questions of research.

3.1.1. Dataset

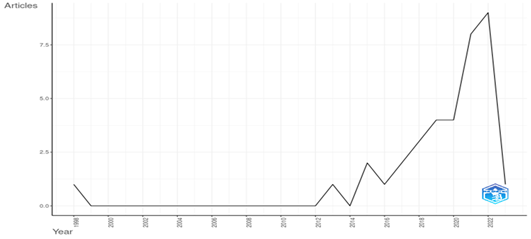

Figure 2 shows the annual

scientific production and highlights the high

interest the scientific awakening of AI in education in the years 21 and 22

there appears to be a decline in the scientific literature on this subject, we

will have to wait for the end of the year in order to

have real data on the publications produced.

Figure 2

Annual scientific production

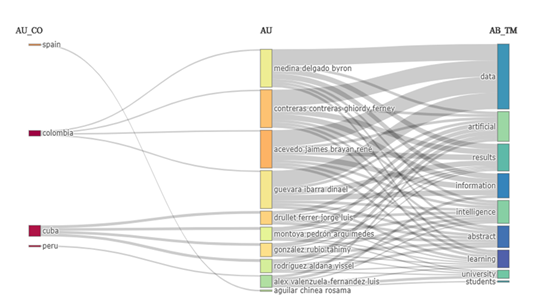

Figure 3 shows the so-called three-field

graph (Sankey diagram), in this case, country, author and abstract and their

interactions with each other. The graph highlights visually the main transfers

between countries, actors and concepts which have in

the summaries. The width of the arrows in the chart is proportional to the

amount of flow.

Figure 3

Sankey diagram

It can be seen that Colombia

and Cuba are the countries where there is the highest production of scientific

use of terms related in the abstracts themselves to AI concepts, such as data,

artificial, intelligence, or learning and are the countries that bring together

the leading researchers, although in Spain and Peru, there are also some

researchers in this field type of issues.

3.1.2. Sources

Concerning the dispersion of

scientific literature, Bradford's Law confirms that if scientific journals are

ordered in a decreasing sequence of productivity from articles on a specific

field, these can be divided into a core of journals that The Bradford core area

(Bradfordcore-zone 1) and various clusters or zones (zones 2 and 3) containing approximately the same number

of items as the kernel, where the number of journals in the core and successive

zones is in a ratio relationship of 1: n: n2, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1

Bradford Core

|

MAGAZINE |

Ranking |

Freq |

Freq Acum |

Zone |

|

Tecnura |

1 |

5 |

5 |

Zone 1 |

|

Revista cubana de ciencias informáticas |

2 |

4 |

9 |

Zone 1 |

|

Formación universitaria |

3 |

2 |

11 |

Zone 1 |

|

Revista universidad y sociedad |

4 |

2 |

13 |

Zone 2 |

|

Academo (asunción) |

5 |

1 |

14 |

Zone 2 |

|

Actualidades investigativas en educación |

6 |

1 |

15 |

Zone 2 |

|

Diseases of the colon & rectum |

7 |

1 |

16 |

Zone 2 |

|

Educación |

8 |

1 |

17 |

Zone 2 |

|

Fem: revista de la fundación educación

médica |

9 |

1 |

18 |

Zone 2 |

|

Horizontes revista de investigación en

ciencias de la educación |

10 |

1 |

19 |

Zone 2 |

|

Información tecnológica |

11 |

1 |

20 |

Zone 2 |

|

Ingeniería electrónica, automática y

comunicaciones |

12 |

1 |

21 |

Zone 2 |

|

Ingeniería industrial |

13 |

1 |

22 |

Zone 2 |

|

Ingeniería y desarrollo |

14 |

1 |

23 |

Zone 2 |

|

Inter disciplina |

15 |

1 |

24 |

Zone 3 |

|

International Journal

of Morphology |

16 |

1 |

25 |

Zone 3 |

|

Propósitos y representaciones |

17 |

1 |

26 |

Zone 3 |

|

Revista cientifica |

18 |

1 |

27 |

Zone 3 |

|

Revista cubana de educación superior |

19 |

1 |

28 |

Zone 3 |

|

Revista cubana de informática médica |

20 |

1 |

29 |

Zone 3 |

|

Revista digital de investigación en

docencia universitaria |

21 |

1 |

30 |

Zone 3 |

|

Revista iberoamericana de tecnología en

educación y educación en tecnología |

22 |

1 |

31 |

Zone 3 |

|

Revista panamericana de salud pública |

23 |

1 |

32 |

Zone 3 |

|

Revista peruana de ginecología y

obstetricia |

24 |

1 |

33 |

Zone 3 |

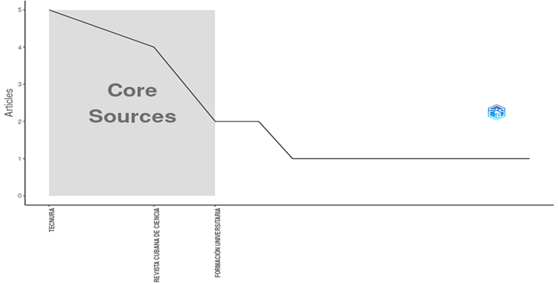

According to this law (Figure

4), it is observed that such a dispersion does not exist, since almost all of

the publication frequency is grouped into three journals (those of the Bradford

core): Tecnura, Revista

Cubana de Ciencia, and Revista de Formación Universitaria, all Latin American, This

shows that scientific production on AI has its origins in South America.

Figure 4

Bradford's Law

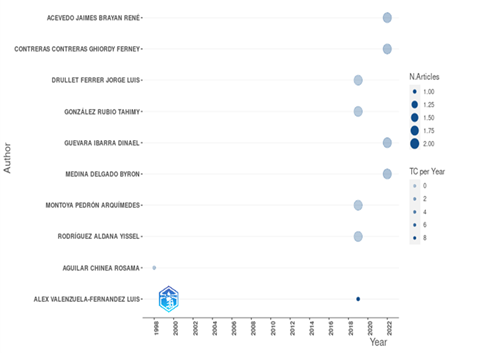

3.1.3. Authors

Figure 5 demonstrates that

scientific production basically starts at the beginning of 2019, but it has

only one author: Alex Valenzuela-Fernandez, the one who accounts for most of

this annual production.

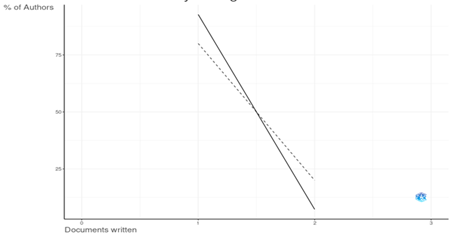

As far as personal

productivity is concerned, Lotka's law is not verified in this case (Fig. (6),

which states that a small number of authors publish a significant amount of

documents, i.e. it states a quantitative relationship between the authors and

the documents, and contributions produced in a given field over a given period

of time, since in a given field the in this case, there are many authors (a

total of 102 authors) who only sign two articles, scientific productivity is

therefore low.

Figure 5

Scientific production of the authors in recent years

Figura 6

Lotka's Law

3.1.4.

Documents

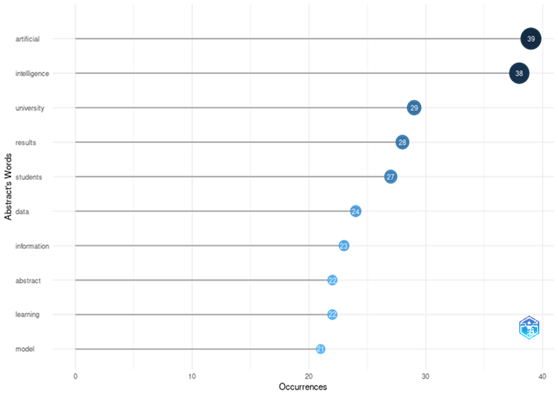

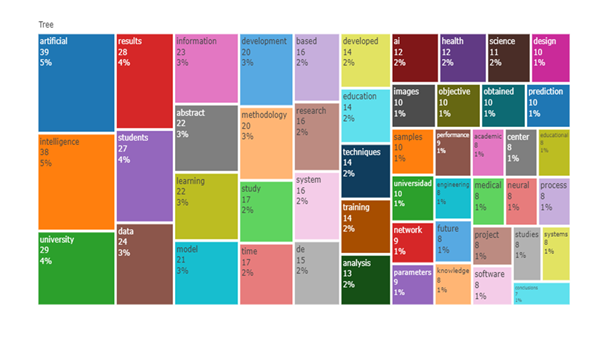

In the analysis concerning

documents, figure 7 shows the most frequent words used by the authors in this

case in the abstracts, with artificial and intelligence being the most

important most commonly used, along with university,

results and students, although in a smaller proportion lower.

Figure 7

Most relevant terms

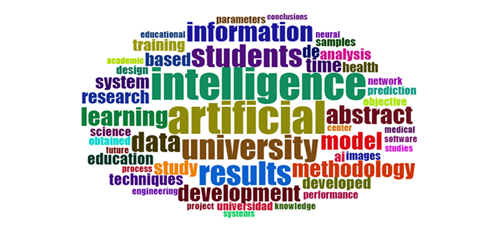

Similar results can be seen in

the figure for the most common word cloud (Figure 8) which is also considered

to be a good formula for identifying the research topics of a scientific domain

(Li et al, 2021), in this case focusing on the 50 keywords, which include terms

extracted from abstracts and in Treemap (Figure 9),

which arranges the data hierarchically and has the structure of a tree in where

the data is organised in nested rectangles (one

inside the other). The size of the rectangle corresponds to the value of the

category or subcategory.

Figure 8

Word cloud

In the word cloud,

"artificial" (39 times), "intelligence" (38 times) stand

out, "University" (29 times) and others such as "results"

or "students" are also important, although they have fewer

repetitions. It is relevant to note that the three most common words are the

variables investigated in this study.

Figure 9

Treemap

3.2. Bibliometrix

Structural Analysis for R Studio Cloud

3.2.1. Conceptual structure

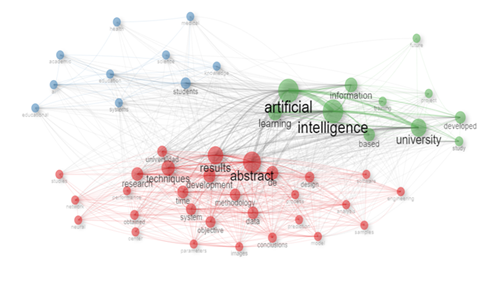

Figure 10 shows a word

co-occurrence matrix, taking into account that two words

co-occur when they appear simultaneously in the same document; two words

co-occur when they appear simultaneously in the same document, and when two

words co-occur when they appear simultaneously in the same document, words will

be more closely linked or associated with each other the greater the

co-occurrence between the words.

Therefore, the size of the

link between two words in a network will be proportional to theco-occurrence of these two words in the set of

documents to be taken as the basis for the sample. In this case, three

co-occurrence groups emerge, which are represented by three different colours in three clusters.

Figure 10

Cooccurrence of words

Figure 10 shows clusters of colours representing words that also use other authors

within the same cluster. For example, in the green cluster, it is observed that

the most commonly used terms are intelligence,

artificial and university and other authors also use them. This is repeated in

the other clusters, indicating patterns which reflect trends and concepts of

research interest.

3.2.2.

Social structure

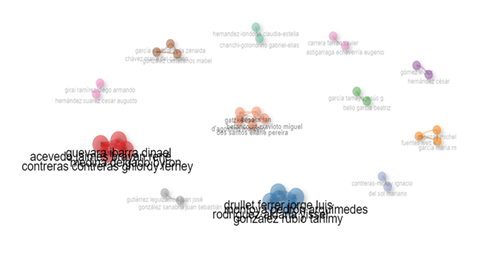

Figure 11 is based on the

collaborative network or co-signing of publications, in this case between

authors. It shows that there is very little collaboration between them. The

fact that they form small collaborative sub-groups is not conducive to research

either.

Figure 11

Collaboration network

3.3. Results obtained from the

Brandwatch social listening software

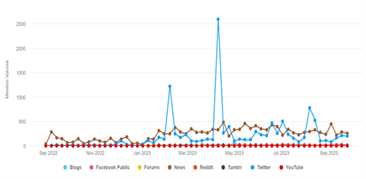

In order to carry out this part of the research, 13,107 authors

were analysed and one total of 27,735 mentions in

networks.

As for the sources of content,

Figure 12 shows the total number of mentions from September 22 to 23, showing

that the highest volume of content (interactions) in May on the Twitter

network, which can be justified by the because on 25 May 2023, UNESCO mobilised Ministers of Education from all over the world

for a coordinated response to ChatGPT, in response to the rapid emergence of

powerful new generative AI tools to explore the opportunities, immediate and

far-reaching challenges and risks that AI applications pose to the education

systems.

Figure 12

Sources of content

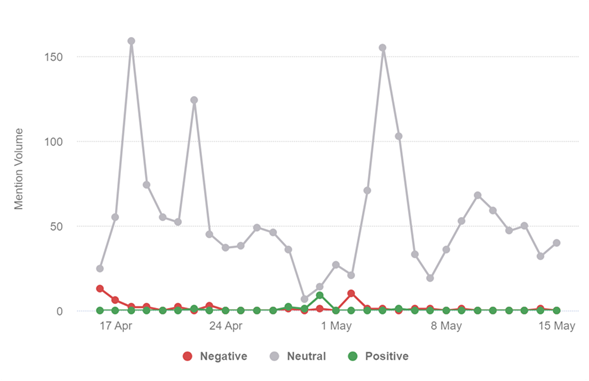

In terms of the sentiment that

AI generates in society, understood as the number of total mentions over time

broken down by sentiment, figure 13 shows how there are many oscillations at

certain times of the year, but the tone is predominantly neutral in most of the

mentions, not standing out in any of them, nor did it have any strong feelings

of positive or negative, perhaps because society has not tested AI and cannot

value.

Figure 13

Sentiment over time

The topic wheel, in Figure 14,

analyses frequently used words and phrases in networks, allowing one to easily

see how the main themes (the inner ring) are related to the sub-themes (the

outer ring), highlighting how the AI relates to the sub-themes (the outer

ring), and highlighting how the AI relates in mentions made with students,

teachers and Chat Gpt, and something similar happens

to Chat Gpt which is related to university. In any

case, terms do not arise studied by the scientific community as AI and Chat GPT

tools, and therefore it is noted that the concern in networks and in the

scientific community about the use of AI in education goes in different

directions.

Figure 14

Topic Roundtable

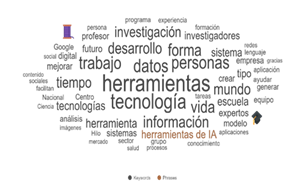

Figure 15 shows the cloud of

words, phrases and entities that are found commonly in the mentions of the

selected time period, highlighting tools, technology,

data, information and people, among others, here too there is no coinciding

with the word cloud derived from scientific studies.

Figure 15

Word cloud

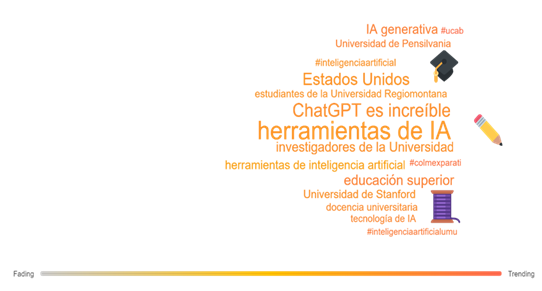

In terms of words and phrases

commonly found in the mentions of the selected time period, delineated

according to whether they are trending or losing the most important of these

are shown in Figure 16, where we can see that all of them are in the zone trending

topic, i.e. AI is trending in the networks but for objectives such as tools or Gpt Chat.

Figure 16

The trend of the themes

4. Discussion and

Conclusions

The incorporation of AI in university studies

generates a broad debate between teachers-researchers, students

and society in general.

Thus, it has been found that

at the scientific level, authors have addressed this issue from different

perspectives, discussing both the opportunities offered by AI and the

challenges it offers ethical and social concerns associated with its

implementation. The use of AI should be treated as a method of teaching

innovation that can generate benefits for students and teachers. Students, in

many cases, stem from the personalised approach that

allows for highly personalised learning for the

learner, but it is also necessary to have.

The Commission has identified

some shortcomings, including how to control misuse, however, few authors are

researching AI in these areas. Scientific production over the last five years

has been low and the number of scientific papers produced has been the main focus on the use and development of the same in certain

areas of degrees related to medicine, electronics or linguistics, but not in

how they apply this intelligence and its tools in new teaching methods.

It is also worth noting that

most of this scientific output is concentrated in Latin American countries and

that there has been virtually no research in Europe on AI and its use in

education, with the authors bearing little relation to each other in terms of

their work.

The concepts most studied by

scientists are grouped into three clusters where terms such as AI, outcomes, or

students are highlighted, but no study is done on the tools that allow AI to be

managed, which also means that these published studies usually remain mere

descriptions of the use of AI in certain learning situations.

On the contrary, social

listening gives primacy to the tools, leaving aside

concepts such as results or yields, which are not talked about in networks, nor

about its application in certain sectors, giving importance to how it should be

used in a tool such as GPT Chat. Feelings are neutral, which also indicates that

there is still a long way to go scientifically so that society can give its

opinion in networks and awaken emotions and feelings.

The study has several

limitations, the main one being that it was carried out on dates when

there was beginning to be talk of the use of some of

the AI tools in specific fields of the university, such as the development of

the so-called Final Degree Projects, or including in the conduct of tests and

examinations, which started to generate a debate on the need to change teaching

methodologies again. Possibly in the near future, lines of research stemming

from the IAC will focus on this, ignoring the misuse that can be made by

students and the excessive control to be performed by teachers to ensure that

this does not happen.

On the other hand, we have not carried out a

quantitative analysis, but a bibliometric analysis.

The WOS database and another

analysis based on social listening, but despite these limitations, this study

will allow a discussion on the EAI and, above all, how it is scientific studies

need to advance in terms of AI tools applicable to university studies so that

society can also have a say on it.

In short, the balance is going

to point to more benefits in terms of AI use than disadvantages, but scientific

studies are needed to demonstrate this for the whole of the university

community to start using AI tools regularly in their academic teaching processes,

as has been the case years ago with other types of progress technology, which

has subsequently become true allies of teachers, such as the m-learning, which

was able to take advantage of Internet content through devices mobile

electronic devices and has incorporated them as a new educational strategy.

Recent research suggests that

AI will be the breakthrough in education and training, the teaching-learning

process, as well as the driving force behind what is now being called the

"learning process".

Education 4.0 (Fidalgo-Blanco et al., 2022;

Ramírez-Montoya et al., 2022). Will this be the case and will

we be able to talk about Education 4.0 in a few years?

Author´s Contribution

Conceptualisation: S.M.-G. and A.B.-M.; Data curation:

S.M.-G.; Formal analysis: S.M.-G.; Research: A.B.-M.; Methodology: S.M.-G.;

Project management: A.B.-M.; Resources: A.B.-M.; Software: S.M.-G. and A.B.-M.;

supervision: S.M.-G. and A.B.-M.; validation: S.M.-G.; visualisation: A.B.-M.;

editing - original draft: S.M.-M.G.; proofreading and editing: S.M.-G. and

A.B.-M.

References

Alonso-de-Castro,

M.G., & García-Peñalvo, F.J. (2022). Successful educational methodologies: Erasmus+

projects related to e-learning or ICT. Campus Virtuales, 11(1),

95-114. https://doi.org/10.54988/cv.2022.1.1022

Aria, M., & Cuccurullo,

C. (2017). Bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping

analysis. Journal of Informetrics, 11(4),

959-975. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2017.08.007

Arksey H., & O

́Malley L. (2005). Estudios

de alcance: hacia un marco metodológico. International Journal

of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19-32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

Barquero Morales, W. G. (2022). Análisis PRISMA como metodología para

revisión sistemática: una aproximación general. Saúde Em Redes, 8(sup1), 339–360. https://doi.org/10.18310/2446-4813.2022v8nsup1p339-360

Cambria, E. (2016). Affective computing and sentiment

analysis. IEEE Intelligent Systems, 31(2), 102-107. https://doi.org/10.1109/MIS.2016.31

Fajardo Aguilar, G. M.,

Ayala Gavilanes, D. C., Arroba Freire , E. M., &

López Quincha , M. (2023). Inteligencia Artificial y la Educación

Universitaria: Una revisión sistemática. Magazine De Las Ciencias:

Revista De Investigación E Innovación, 8(1), 109–131. https://doi.org/10.33262/rmc.v8i1.2935

Fidalgo-Blanco, A., Sein-Echaluce, M.L., & García-Peñalvo, F.J. (2022).

Método basado en Educación 4.0 para mejorar el aprendizaje: Lecciones

Aprendidas de la COVID-19. RIED, 25(2), 49-72. https://doi.org/10.5944/ried.25.2.32320

Halili, S. H. (2019). Technological advancements in

education 4.0. The Online Journal of Distance Education and E-Learning, 7(1),

63–69. https://bit.ly/46dpmR4

Herrera, L.C., Majchrzak, T.A., Thapa, D. (2022). Principles

for the Arrangement of Social Media Listening Practices

in Crisis Management. In: Sanfilippo, F., Granmo, OC., Yayilgan, S.Y., Bajwa, I.S. (eds) Intelligent Technologies

and Applications. INTAP 2021. Communications in Computer and Information

Science, vol 1616. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-10525-8_22

Hinojo-Lucena, F.-J.,

Aznar-Díaz, I.; Cáceres-Reche, M.-P., &

Romero-Rodríguez, J.-M. (2019). Artificial Intelligence in Higher Education: A

Bibliometric Study on its Impact in the Scientific

Literature. Education Science 9, 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9010051

Jimbo-Santana, P., Lanzarini, L. C., Jimbo-Santana, M., & Morales-Morales,

M. (2023). Inteligencia artificial para analizar el rendimiento académico en

instituciones de educación superior. Una revisión sistemática de la literatura.

Cátedra, 6(2), 30–50. https://doi.org/10.29166/catedra.v6i2.4408

Li, J., Goerlandt, F., &

Reniers, G. (2021). An overview of scientometric

mapping for the safety science community: Methods, tools, and framework. Safety

Science, 134, [105093]. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssci.2020.105093

Lu, L. L. & Harris, L.A. 2018. Artificial

Intelligence (AI) and Education. FOCUS:

Congressional Research Service. Consultado en https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/IF10937.pdf

Martínez-Comesaña, M., Rigueira-Díaz, X., Larrañaga-Janeiro, A.,

Martínez-Torres, J., Ocarranza-Prado, I., & Kreibel, D. (2023). Impacto de la inteligencia artificial

en los métodos de evaluación en la educación primaria y secundaria: revisión

sistemática de la literatura. Revista de Psicodidáctica,

28(2), 93-103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psicod.2023.06.001

Moreno, L., & Pedreño,

A. (2020). Europa frente a EE.UU. y China. Prevenir

el declive en la era de la inteligencia artificial. KDP. https://bit.ly/3PFeOS2

Page, M. J., Mckenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D. & Moher, D.

(2021). Declaración PRISMA 2020: una guía

actualizada para la publicación de revisiones sistemáticas. Revista Española de

Cardiología, 74(9), 790–799.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.recesp.2021.06.016

Ramírez-Montoya, M.S.,

Castillo-Martínez, I.M., Sanabria-Z, J., & Miranda, J. (2022). Complex thinking

in the framework of education 4.0 and open innovation-a systematic literature

review. Journal of Open Innovation, 8(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc8010004

Salas-Pilco, S. Z., & Yang, Y. (2022). Artificial

intelligence applications in Latin American higher education: a systematic

review. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education,

19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-022-00326-w

Song, P. & Wang, X. (2020). A bibliometric

analysis of worldwide educational artificial intelligence research development

in recent twenty years. Asia Pacific Education Review, 21(3), 473–486. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-020-09640-2

Stieglitz, S., Mirbabaie,

M., Ross, B. & Neuberger, C. (2018). Social media analytics—Challenges in

topic discovery, data collection, and data preparation. International

Journal of Information Management, 39, 156–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2017.12.002.

Telefónica (2019). Informe

Things Matter 2019. La

experiencia del usuario de Internet de las Cosas en España. https://iotbusinessnews.com/download/white-papers/TELEFONICA-white-paper-things-matters-2019.pdf

Zawacki-Richter, O., Marín, V.I., Bond, M., &

Gouverneur, F. (2019). Revisión

sistemática de la investigación sobre aplicaciones de inteligencia artificial

en la educación superior: ¿dónde están los educadores? Revista Internacional de Tecnología Educativa en la Educación Superior, 16(1),

1-27.