Booktok Time: Characterization of New Videos for

Mobile Reading Promotion

La hora del Booktok:

caracterización de nuevos vídeos para la promoción lectora en el móvil

La hora del Booktok: caracterización de nuevos vídeos

para la promoción lectora en el móvil

Dr. José Rovira-Collado. Profesor Permanente

Laboral. Universidad de Alicante. España

Dr. José Rovira-Collado. Profesor Permanente

Laboral. Universidad de Alicante. España

Dr. Francisco Antonio Martínez-Carratalá. Profesor Asociado.

Universidad de Alicante. España

Dr. Francisco Antonio Martínez-Carratalá. Profesor Asociado.

Universidad de Alicante. España

Dr. Sebastián Miras. Profesor Ayudante

Doctor. Universidad de Alicante. España

Dr. Sebastián Miras. Profesor Ayudante

Doctor. Universidad de Alicante. España

Received: 2024/06/12 Reviewed 2024/07/03 Accepted: :2024/12/17 Online First: 2024/12/20 Published: 2025/01/07

Cómo citar este artículo:

Rovira-Collado,

J., Martínez-Carratalá, F. A., & Miras, S. (2025). La hora del Booktok: caracterización de nuevos vídeos para la promoción

lectora en el móvil [Booktok Time: Characterization of New Videos for Mobile Reading Promotion]. Pixel-Bit. Revista De Medios Y Educación, 72, 180–197. https://doi.org/10.12795/pixelbit.107744

ABSTRACT

Booktoks are short videos about reading on TikTok, heirs to

literary blogs and booktubers. The vast majority are created and consumed on

mobile devices. This research conducts a qualitative analysis of content in

digital contexts regarding Spanish booktoks. Based on

a previous sample of 500 videos, selected through the platform's algorithm

suggestions, analysis is carried out on n=299 videos to identify their main

characteristics and differences with previous spaces. Extension, audience,

quantity of comments, tags used, and profile typology are analyzed.

Subsequently, various specific analyses are proposed, such as the most used

tags; the most followed profiles from our selection (n=30

)indicating their characteristics and interaction with other digital

platforms; and a detailed analysis of several videos to exemplify their

characteristics. Finally, n=10 specific booktoks are

selected to present the differences with previous models of reading promotion

on the Internet. New dynamics are identified, confirming that mobile devices

result in shorter videos about books, distancing us from literary reflection.

Los booktoks son vídeos breves

sobre lectura en TikTok, herederos de los blogs literarios y los booktubers. La

gran mayoría se crean con el móvil, que es también su espacio natural de

reproducción. Esta investigación realiza un análisis cualitativo del contenido

en contextos digitales sobre los booktoks en español. A partir de una muestra

previa de 500 vídeos, seleccionados a través de las sugerencias del algoritmo

de la plataforma, se realiza un análisis de n=299 vídeos para identificar sus

principales características y las diferencias con los anteriores espacios. Se

analiza la extensión, la audiencia, la cantidad de comentarios, las etiquetas

usadas y la tipología de los perfiles. Posteriormente, se proponen distintos

análisis concretos como las etiquetas más usadas; los perfiles más seguidos de

nuestra selección (n=30), señalando cuáles son sus características y su

interacción con otras plataformas digitales; y el análisis pormenorizado de

varios vídeos para ejemplificar las características. Por último, se seleccionan

n=10 booktoks concretos para presentar las diferencias con anteriores modelos

de promoción de la lectura en Internet. Se identifican nuevas dinámicas y se

confirma que el móvil supone una menor duración en los vídeos sobre libros que

nos aleja de la reflexión literaria.

KEYWORDS · PALABRAS CLAVES

BookTok; TikTok; Reading Promotion; Social Media;

Mobile Devices; Digital Reading; Digital Competence; Content Creation

BookTok; TikTok; Promoción lectora; Redes sociales;

Dispositivos móviles; Lectura digital; Competencia digital; Creación de

contenido

1. Introduction

The concept of social reading in digital environments

(Cordón-García et al., 2013) encompasses all spaces dedicated to the promotion

or mediation of reading on the Internet, many of which are virtual reading epitexts (Lluch et al., 2015). These epitexts

are understood as digital documents and resources created by publishers,

educational institutions, or individuals “in order to sell books and promote

reading online, of various types, with communicative functions such as

commenting, disseminating, modifying, and expanding” (p.798) the information

about a literary text, given that they provide significant information about

reading, literature, and books in general (Hernández Heras et al., 2022). Since

2020, two spaces have gained the most attention among younger generations

(Sanz-Tejeda & Lluch, 2024): bookstagrammers

and booktoks. The former are native to Instagram,

where “a group of bibliophiles uses the platform to celebrate the book as an

aesthetic object, as a cult item in itself.” Thus, they “turn their Instagram

profiles into catalogues of artistic photographs featuring books that, in some

way, they idolise and recommend to other readers” (Quiles, 2020, p.16). The

second group, which is the central object of this research, consists of short

videos about reading and literature on TikTok, a video-based social

network designed to create, share and enjoy content primarily through mobile

devices. These new videos specifically designed to promote reading are an

evolution of previous text-based models such as literary blogs and forums,

(García & Rubio, 2013); video-based formats like booktubers, which

are their direct predecessors (Sorensen & Mara, 2014; Rovira-Collado, 2017;

Tomasena, 2019; Paladines & Margallo, 2020); or

hybrid spaces that combine photographs and videos (reels or stories)

that foster discussion about reading, such as the aforementioned bookstagrammers (Sánchez & Aparicio, 2020). The

latest social media usage reports (IAB, 2022) confirm that both platforms are

experiencing significant growth and projection. However, booktoks

have garnered the most attention and are increasingly engaging younger readers.

In 2020, the publishing house Penguin already recommended key booktoker profiles, and various reports and studies

(Nielsen, 2021; Talbot, 2023) highlight the growing use of these videos as

promotional tools within the publishing industry, to influence the next reading

choices of their viewers.

Booktubers, as a direct

predecessor of using videos to promote reading online, have been thoroughly

analysed in recent years (Vizcaíno-Verdú;

Contreras-Pulido & Guzmán-Franco, 2019; Tomasena,

2021). This community focuses on “recommending books and promoting reading by

tailoring their messages to the videoblog format.” They allow us to “delve into

new youth practices outside the classroom that relate to book promotion and

critical, informed expression about content, formats, genres, and authors” (Vizcaíno-Verdú; Contreras-Pulido & Guzmán-Franco, 2019,

p.1). For years now, young readers’ literary criticism on the Internet has

shifted from written reviews to video reviews (Paladines & Aliagas, 2023), with booktok

emerging as the space with the greatest potential.

One of the main differences between these videos and booktubers

lies in the mobile device as their natural medium, enabling massive audiences

and the emergence of new figures such as influencers—celebrities whose

status is built through their presence on social networks (Abidin, 2020).

Moreover, the ease of sharing and consuming this content on mobile devices has

given rise to a new concept: “content creators”, individuals who regularly

publish videos on these platforms, covering a wide range of topics in order to attract large audiences. The number of views and

visibility of these videos (Cordón-García & Gómez-Díaz, 2019) allows these

creators to earn financial compensation based on the number of reactions,

comments and views, with some of them even earning small fortunes.

Various studies have already focused on this new

phenomenon of literary mediation through the Internet, particularly in the

English-speaking world (Merga, 2021; Martens et al.,

2022), confirming that it is an area of interest for social reading and

literary communication online. A recent systematic review of both research

methods and its findings on reading in online environments, such as Instagram

and TikTok, highlights their differences and innovations in usage

(Sanz-Tejada & Lluch, 2024), as well as the shared elements with the

earlier dynamics mentioned above. However, there is still no detailed

description of its significance within the Spanish-speaking context.

Therefore, the primary objective of this research is

to propose a characterisation of Spanish-language booktoks.

Secondary objectives include describing specific uses of these videos and

identifying the main differences from previous models.

2. Methodology

This research offers a selection of Spanish-language booktoks and a detailed content analysis to identify

new uses and differences compared to other types of virtual reading epitexts. Kozinets’ (2021) netnographic models were applied to establish the selected

corpus. Initially, over 500 booktoks were

curated and grouped into a specific list (https://www.tiktok.com/@joseroviracollado/collection/Booktok-7193946691401796357) in order to

identify the most frequently used tags and the general characteristics of these

videos. This selection was based on recurrent navigation through a specific

profile and systematic searches to identify videos relevant to the research.

The profile used was created in February 2020, a month

before the global lockdown caused by COVID-19, during which TikTok

experienced significant growth in both registered users and published videos.

The initial contact and first video suggestions were mediated by the platform’s

algorithm. It is worth noting that the TikTok algorithm is designed to

foster addiction, particularly among younger viewers (Wang & Guo, 2023).

Although the platform includes advertisements aimed at preventing prolonged

usage, the risks of "infinite scrolling" are considerable, especially

for young users who may spend hours watching short videos (Petrillo, 2021;

Natarajan, 2024). TikTok offers two main options for viewing content:

"Following," which displays content from followed profiles, and

"For You," which suggests new videos based on the algorithm’s

assessment of user preferences. These two access routes to new content have

also been adopted by platforms such as X (formerly Twitter) and

the emerging Blue Sky, to organize users’ timelines into two streams:

one based on followed accounts and the other curated by the algorithm.

During the initial stages of using the tool, between

2020 and 2022, efforts were made to force the algorithm to predominantly

display content related to reading and books. Periodic searches were conducted

using terms such as "book," "booktok,"

"lectura" (reading), "libros" (books), and "literatura"

(literature). It is noteworthy that the platform does not always prioritise the

most-viewed videos, but also tends to promote trending

or recent content. Profiles producing such videos were followed from the initial

stages of the study, and these videos were marked with a "like" (a

red heart icon). Despite the continued appearance of unrelated content during

routine browsing, over 50% of the videos displayed were related to the research

topics. As of June 2024, the profile used follows more than 7,500 accounts, of

which over 6,000 are aligned with this research focus. During the data

collection process, TikTok introduced an additional feature alongside

the red heart: a "favourites" icon (a yellow tag), which functions

similarly to Instagram’s option for organising content into specific

collections.

Since navigation primarily occurs via mobile devices,

the results displayed depend on the algorithm assigned to each account.

Consequently, TikTok’s algorithm may alter the outcomes of any given

search (Siles et al., 2022). Unlike other platforms such as YouTube,

where searches for specific terms yield more consistent results, TikTok

may produce different outcomes across devices due to its integration with the

user’s mobile phone environment. The informational biases inherent to digital

platforms, stemming from their lack of neutrality, were considered in this

research (van Dijck, 2013; Hepp, 2020). Factors such as the browsing history of

the profile used, interconnection with other programs, cookies, and social

networks may influence the results presented (Fisher, 2022).

Once the initial corpus of 500 videos was compiled,

additional studies on TikTok were reviewed to compare different

procedures for classifying videos (Caldeiro-Pedreira

& Yot-Domínguez, 2023; Rovira-Collado & Ruiz-Bañuls, 2022). With this context in mind, the research team

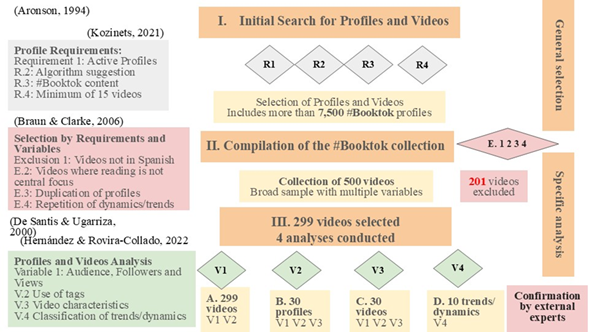

implemented the process outlined in Figure 1 to complete the selection of booktoks.

Figure 1

Flowchart of Booktok

selection

Source: Own work

Following Kozinets’ netnographic approach, criteria for selection and analysis

were established (Turpo Gerbera, 2008). Additionally,

a thematic qualitative analysis was conducted (Aronson, 1994), and the research

question was formulated in alignment with the selected objectives. The initial

500 videos were individually analysed by members of the research team, followed

by a collective discussion of their general characteristics. This study took

place between November 2023 and March 2024. At this point in the research, the

team decided not to include an analysis of audience interactions and comments

(Roig-Vila, Romero-Guerra & Rovira-Collado, 2021), which may be addressed

in future publications. Furthermore, the categories that were established,

together with the results obtained, were compared against feedback from

platform users with an interest in the online promotion of reading. This

external team included three senior researchers and

three early-career researchers interested in various uses of Booktok.

Specific data were collected for each selected video

as well as for the profiles responsible for publishing them, including

Duration, Audio, number of Tags along with the names of all the tags, Audience

metrics, such as the number of followers and the number of users followed by

the profile; for the videos, the following data were also collected: number of

Views, Likes, Shares, and Comments. Moreover, a specific typology was

established to classify content into categories, such as: Print Book, Digital Book,

People: Female, People: Male, Spaces, Digital-Others, as detailed in the

figures and tables provided in the Zenodo Annex. As for the Audio category, it

is determined whether the recording is user-created or rather pre-recorded

music provided by the platform. For the Profiles, it is also determined whether

users provide information about accounts they may have on other platforms, such

as Instagram (IG), Wattpad (Wtt), Portal,

Goodreads (G), YouTube (YT), Twitter (Tw), and Facebook

(FB).

From the initial 500 videos, specific criteria were established

for the first selection: 1. Profiles had to be active; 2. Videos had to be

algorithmically recommended in the "For You" section; 3. The content

had to be taggable with #booktok; 4. Profiles needed a minimum level of

activity (at least 15 videos). Additionally, all videos had to be publicly

accessible without requiring a login to ensure the privacy of each account. Descriptive

variables (Braun & Clarke, 2006) and exclusion criteria were

also defined: the videos had to be in Spanish or created by Spanish-speaking profiles, and centred on reading-related content. With regard to the language used, some videos in English

were included to highlight emerging trends, which will be discussed later. Many

videos were excluded because they originated from the same profiles or featured

repetitive trends frequently appearing in timelines, resulting in a final

corpus of 299 videos (201 videos discarded). A subsequent individual selection

was made to identify the most significant videos (30) and profiles (30), focusing

on the following variables (DeSantis & Ugarriza,

2000; Hernández & Rovira-Collado, 2023): V1 Audience, Followers and Views;

V2 Use of Tags; V3 Video Characteristics; and V4 Classification of procedures

and dynamics. This process resulted in a final list of 10 videos.

Finally, distinct categories were defined for the

description of the videos, along with the main descriptive data for each video

and profile in order to refine the analysis, which

started in November 2023.

3. Analysis and

Results

3.1. Global descriptive

results for the 299 videos

Some of the descriptive results are included as an

external annex on Zenodo (https://zenodo.org/records/14507130). In Zenodo Table

I, among the total of 299 videos analysed, the average duration was observed to

be 39.59 seconds, with a range from a minimum of 4 seconds to an outlier

maximum of 553 seconds. Ten videos were identified as slideshow presentations,

likely originating from other platforms, while the remaining 289 were dynamic.

The percentage of videos shorter than 39 seconds constitutes 67.82% of the

total dynamic videos (299), which emphasises brevity as a defining feature of

the platform's content. Regarding audio content, 175 videos (58.53%) include

music, whereas in 124 videos (41.47%), it is the protagonist who directly

addresses the viewer using their own voice.

In total, the 299 videos achieved 53,027,954 views (M

= 177,351.02), 3,823,354 likes (M = 12,827.49), 130,484 shares (M = 439.34),

and 21,445 comments (M = 72.21).

Concerning Typology or central element, the most

frequently featured subject is the Book (166 videos; 55.52%), followed

by Girl/Book (61 videos; 20.40%) or Girl alone as the protagonist

(23 videos; 7.69%). In contrast, less common options include the use of Kindle

or other digital reading devices (3 videos; 1%). The print book stands out as

the central feature in 245 booktoks (81.94%)

across the different typologies. Out of the 299 videos, only 278 distinct

profiles are represented, as some profiles appear multiple times across

different videos. The gender of the protagonist is identified in 242 videos

(221 women and 21 men). Additionally, the dataset includes the identification

of 5 publishing houses, 5 institutions, 5 bookshops, 3 reading communities such

as “Qué leer,” and 4 categorised as “others.”

Participation on other platforms as part of a transmedia strategy was also

noted.

3.1.1 Most used tags

Table 1 shows the 25 most frequently used tags across

the 299 analysed videos. Tags work as a fundamental tool for locating these

videos, as they do in similar spaces like literary blogs (García & Rubio,

2013). A total of 1,137 tags were recorded, which were used 2,945 times overall

(this count was used to calculate Absolute Frequency). These 25 key terms

account for 40.81% of the total tags collected (while the remaining 1,112 tags

represent 59.19% of the total). The table includes a column showing the total

views associated with each tag according to the platform’s data as of 20

January 2024. The abbreviation B (Billions) is used to denote the vast audience

numbers, with some tags reaching billions of views. It is noteworthy that this

figure has likely increased over this brief period of time

due to the continuous traffic on the platform.

Table 1

25 Most frequently used tags across the 299 analysed

videos

|

Tag (#) |

AF |

AF (%) |

Total views of the Tag on TikTok |

|

booktok |

227 |

7.71 |

144.40B

(Billions) |

|

libros |

108 |

3.67 |

12.70B |

|

books |

98 |

3.33 |

37.20B |

|

booktokespañol |

80 |

2.72 |

3.50B |

|

fyp |

65 |

2.21 |

42,639.60B |

|

booktoker |

64 |

2.17 |

12.80B |

|

libroslibroslibros |

50 |

1.70 |

4.00B |

|

bookworm |

47 |

1.60 |

18.00B |

|

librosrecomendados |

41 |

1.39 |

2.90B |

|

book |

40 |

1.36 |

18.90B |

|

librostiktok |

40 |

1.36 |

3.30B |

|

bookish |

35 |

1.19 |

18.80B |

|

bookstagram |

34 |

1.15 |

1.50B |

|

parati |

32 |

1.09 |

6,513.90B |

|

booktokespaña |

30 |

1.02 |

0.56B |

|

lectura |

30 |

1.02 |

2.80B |

|

leer |

25 |

0.85 |

2.20B |

|

booklover |

22 |

0.75 |

3.40B |

|

libro |

22 |

0.75 |

2.80B |

|

bookrecommendations |

21 |

0.71 |

10.40B |

|

reading |

21 |

0.71 |

13.60B |

|

bookclub |

19 |

0.65 |

14.10B |

|

literatura |

18 |

0.61 |

1.50B |

|

foryou |

17 |

0.58 |

25,011.20B |

|

lectores |

14 |

0.50 |

2.10B |

Source: Own work

The tags are organised by their frequency of appearance

in the 299 videos, with “booktok” being the most

common, as it defines the category. This tag appears 277 times (92.64% of the

total) and has an Absolute Frequency of 7.71 out of the 2,945 tags. Other

frequently appearing tags in this selection of 299 Spanish-language videos

include “Libros,” “booktokenespañol,” “LibrosLibrosLibros,” “librosrecomendados,”

“booktokespaña,” and “librosTikTok.”

Tags such as “fyp,” referring to “for you page,” “página para ti,” or “para ti,” also appear

with billions of views, serving as strategies to enhance the virality of the

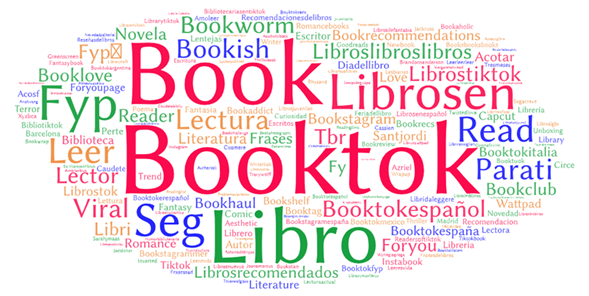

videos. Subsequently, a WordArt visualisation was created based on the 200 most

viewed tags out of the 1,137 used, in order to

highlight the most significant ones.

Figure 2

200 most frequently used tags in the analysed videos

Source: Own work

3.2. Analysis of 30 Reader

Profiles on TikTok

In this second selection, a description is provided for

the 30 most-followed profiles from the list of 299 videos. Global metrics are

analysed, such as the total number of videos published, followers, and views,

along with specific characteristics of each profile or their interaction with

other social media platforms, as shown in Table 2. A detailed description of

the profiles and their names can be found in Table II of the Zenodo Annex.

Table 2

Descriptive characteristics of the 30 most-followed

profiles

|

Descriptors |

Users |

|

AF |

AF (%) |

|

Gender |

Female |

Individual |

23 |

76.67 |

|

|

|

Sisters |

1 |

3.33 |

|

|

Mixed |

Female and Male |

1 |

3.33 |

|

|

|

Various |

1 |

3.33 |

|

|

Male |

Individual |

4 |

13.34 |

|

Social Media |

Only TikTok |

|

8 |

26.67 |

|

|

Instagram |

|

16 |

53.33 |

|

|

Wattpad |

|

1 |

0.33 |

|

|

Web/Portal |

|

11 |

36.67 |

|

|

Goodreads |

|

6 |

20.00 |

|

|

YouTube |

|

4 |

13.33 |

|

|

X (Twitter) |

|

5 |

16.67 |

|

|

Facebook |

|

2 |

0.67 |

|

Videos |

|

|

9,800 |

326.67 |

|

Following |

|

|

6,860 |

228.67 |

|

Followers |

|

|

2,739,571 |

91,319.03 |

|

|

Over 1 million |

|

1 |

3.33 |

|

|

Between 999,999 and 100,000 |

|

5 |

16.67 |

|

|

Between 99,999 and 30,000 |

|

9 |

30.00 |

|

|

Between 29,999 and 10,000 |

|

12 |

40.00 |

|

|

Between 9,999 and 8,900 |

|

3 |

10.00 |

|

Likes |

|

|

45,182,340 |

1,506,078 |

The selection of the most prominent profiles was based

on the thirty users—excluding portals, publishers, or libraries, for

instance—with the highest number of followers. In this regard, as shown in

Table II of the Annex, one user stands out (@fantasyliterature) with the

highest number of followers (1,187,392). The sample is evenly divided, with 50%

of profiles having more than 30,000 followers and the remainder ranging between

29,999 and 8,900 (with the interval between 29,999 and 10,000 being the most

representative). There is also a notable predominance of women over men, with

female representation accounting for nearly 90%. Among the fifteen profiles

with more than 30,000 followers, only two are male: @sans.reyes

(129,076 followers) and @javierruescas (87,328 followers). Collectively, this

group of content creators on TikTok has produced a total of 9,800

videos, with the most active profiles being @sans.reyes

(975 videos) and @roibooks (969 videos). Ten of these analysed profiles have

uploaded more than 400 videos to their channels. Similarly, it is evident that

these users have built a large community of followers who prefer engagement

through the “Like” option, with the most prominent user in this regard being

@patriciafedz, who has accumulated over 7 million positive interactions on her

content, establishing herself as a true “literature influencer”.

Another aspect considered in the analysis was whether TikTok

served as the primary platform for interaction, or if users relied on other

social media to complement their digital identity. In this case, among the most

prominent profiles, eight users link to another platform in their biography,

with Instagram being the most common (53.33% of cases). When comparing

profiles across both platforms, it is notable that the majority (13 users) have

more followers on TikTok than on Instagram. Nevertheless, it was

noted that most individuals from one platform disseminate their content across

others, tailoring it to the specific nature of each platform; for instance,

other portals related to literary promotion such as Goodreads can also

be found.

3.3. Analysis of 30 standout

videos

Although the platform generates prominent profiles

with thousands of followers—the so-called 'influencers'—our analysis focuses

more on the typology of videos they produce and the innovations they introduce.

For this reason, a further selection of 30 videos was made, with the main data

presented in the following Table 3.

Table 3

General characteristics of the thirty selected videos

|

|

Maximum |

Minimum |

Average |

Total |

|

Duration (in seconds) |

135 |

5 |

39.40 |

1,182 |

|

Views |

2,700,000 |

598 |

534,069.10 |

16,022,073 |

|

Likes |

373,600 |

49 |

72,575.40 |

2,177,262 |

|

Number of comments |

1,843 |

1 |

389,333 |

11,680 |

As in the previous case, Table III in the Zenodo Annex

includes detailed data on the 30 videos, including the full URL for accessing

them, the tags used, the number of views, likes, duration, and comments for

each video

The longest booktok

exceeds two minutes, while the shortest (Video #34) lasts only five seconds.

This short video follows the “What are you reading?” trend, which will be

discussed later. The selection includes videos with low numbers of views (598),

likes (49), and comments (1), which were nevertheless included in order to identify new trends. However, considering the

totals, it is worth noting that these 30 videos collectively have over sixteen

million views, two million likes, and more than eleven thousand comments,

demonstrating their significant audience, with figures surpassing those of

earlier booktubers. The brevity of these videos and their accessibility

through mobile devices are key reasons for their wide reach.

The distribution of the 30 booktoks

by main focus or protagonist is as follows: 13 feature

a Book; 8 Girl/Book; 5 Girl; 2 Boy/Book; 2 Boy;

and 1 Girl/Author. The terms “girl” and “boy” have been used to reflect

the youthful and informal nature of the videos. It is noteworthy that the book

is the central focus in 25 videos, often accompanied by men or women. There are

more videos featuring women as protagonists (14) compared to men (4). However,

this is an unusual finding, as men typically account for less than 10% of these

videos. This is likely due to the inclusion of a few male protagonists with

substantial audiences.

Finally, a final selection was made, based on both the

novelty of the trends and the multimodal elements each video offers, as

analysed in another study (Rovira-Collado, Martínez-Carratalá,

& Miras, 2024). Ten distinct trends were identified in these 10 videos.

Preceding classifications (Tomasena, 2021) were not

adopted in this analysis, allowing for the development of a novel multimodal

classification.

Table 4

Selection of 10

videos and description of their different dynamics/trends

Own work

It is worth mentioning that many of these videos have

a significant audience, with thousands of “likes”. The first example, What

are you reading?,

has far fewer likes but was included because it was one of the first to be

added to the list and most clearly demonstrates a new trend. Along with 2. Fiesta

de seguidores-lectores (Reader Follow Party),

these categories represent two of the most innovative trends compared to

earlier models. Both booktoks are very short

and illustrate the rise of hyper-brief dynamics and, in both cases, the main focus is on books or bookshelves, with very short

recordings accompanied by a specific audio piece in English that gives a title

to these trends. In the first example, only the reverse side of the book spine

is shown at first, revealing just the edges of the pages and making it

impossible to identify the book, only to reveal the cover and title the end of

the clip. The video lasts only five seconds, synced with the audio file

available on the platform: https://www.tiktok.com/music/Whats-this-person-reading-right-now-6904077601871170309. A review of this

audio piece shows that it has been used in over 100,000 similar booktoks, making it a notable new trend

The second example, Fiesta de seguidores-lectores (Reader Follow Party), also relies on a

specific audio recording. In this case, it is a Spanish translation of Reader

Follow Party (https://www.tiktok.com/tag/readerfollowparty), which has been

used over 10,000 times, albeit mostly in English.

The third

video, Libraries, demonstrates professional mediation, where the manager

of a public library (@bibliotecaugena) shares videos about her daily work.

These are also very short; for instance, one video is only 13 seconds long and

introduces several books.

The fourth example, Types of Booktoker,

features a young protagonist discussing books and showcasing different types of

new readers associated with these trends. While not all protagonists are

teenagers, these videos show a generational shift from earlier models.

The fifth

example, Fostering Reading, features Iria and Selene, famous booktubers

and authors of young adult literature, experimenting with new trends on TikTok.

Here, they present their latest book with a popular background song, Naughty

(Alisha Weir & The Cast of Roald Dahl's Matilda the Musical). As in other

cases, the use of specific sounds helps create trends. This song from the

musical Matilda is commonly used to depict pranks or mischievous acts,

with humour being a key aspect of many such videos.

The sixth type,

Editors, is labelled as such because the protagonist self-identifies as

an editor, although the video is more of a humorous take on an ever-growing

wish list of books she has. Interestingly, the video does not prominently

feature books but highlights a passion for reading instead. Once again, the

video’s effect relies on a specific audio clip, “Ding dong”,

where after a dull thud resembling a knock on a door, a female voice mimics the

sound of a bell, marking the protagonist's sudden appearance

Some of the selected dynamics have stronger

connections to YouTube and earlier models. The importance of “content

creation” and the emergence of new “influencers” has already been discussed.

The seventh example, Bookinfluencer, features

Patricia Fernández, who has amassed a significant following by talking about

books. Her videos, like many others, also highlight the importance of the image

she portrays—young, attractive, and relatable—consistent with trends across

other social networks (Calvo-González; San Fabián, 2019; Dezuanni

et al., 2022). This booktok has already

garnered over 200,000 views, 20,000 likes, and numerous comments. @patriciafedz

has a steady production of videos and hundreds of thousands of followers,

thereby firmly establishing herself in this category.

Javier Ruescas is another influencer

who encourages reading and, in addition to being a young adult author, was also

active in former blogs and booktuber communities. On World Book Day,

he usually shares a video about the origins of this event, showcasing his

adaptability to the new medium and engaging a large audience.

The category of Videopoems

is not particularly novel, and it typically involves the previously recorded

voice of a poet, or features someone reciting their verses. In this case,

@marinalcuadrado offers a recording focused on herself, with over 150,000

views. This type of videopoem is more personal,

making poetry more accessible compared to traditional videopoems

on YouTube, which often rely on photomontages.

The final example, So Said...,

represents an intermediate dynamic or trend which focuses on famous quotes,

typically accompanied by static photomontages, remaining very brief. The

selected example highlights the words of the Uruguayan poet Mario Benedetti,

demonstrating how this format can bring literary voices into contemporary

digital spaces.

4. Discussion and

Conclusions

Based on the research question and primary objective,

it is concluded that the various analyses presented enable a detailed

characterisation of Spanish-language booktoks

as new virtual epitexts for promoting reading. From

the global analysis of 299 examples to the specific selections, the study

demonstrates a broad progression that delineates the evolution from earlier

spaces. The first key finding concerns the two primary categories of booktoks. They represent two of the most innovative

#Booktok trends, with books serving as the central focus of both

practices. Although the selected examples are from Spanish-speaking users, the

original tags and audio they use are actually in

English, reflecting their much wider reach and highlighting clear trends within

TikTok.

A brief trajectory can be proposed, starting from

literary forums as the first digital epitexts in 2003

(Lluch & Acosta, 2012), to literary blogs from 2006, which exhibited a wide

variety (García Rodríguez & Rubio González, 2013). This was followed by booktubers,

who experienced their peak between approximately 2011 and 2018 (Tomasena, 2021). Subsequently, from 2014 to 2020, social

reading platforms such as Goodreads replaced former spaces (García-Roca,

2020). By 2016, Bookstagram began to emerge

(Quiles Cabrera, 2020), and since 2020, the rise of Booktoks

has been evident (Guiñez-Cabrera &

Mansilla-Obando, 2022.

The creation of videos and

the analysis of other productions can support the development of digital skills

(Allué & Cassany, 2023)

and previous videos already demonstrated their educational value (Paladines

& Aliagas, 2021). Specific proposals for

integrating TikTok dynamics into classrooms already exist (Blanco Martínez & González

Sanmamed, 2021).

It must be acknowledged that this is a different

category compared to previous models. Some characteristics inferred from the

description provided are:

-These videos are generally much shorter than earlier

ones, enabling quicker consumption but often limiting in-depth literary

analysis. However, their brevity also results in a larger audience, surpassing

figures achieved by previous modalities.

-The primary space for creating and disseminating

these videos is the mobile phone. While some videos can be recorded and edited

using other resources, as was common with booktubers, the vast majority

are created on mobile devices. Numerous editing applications for different

mobile operating systems have emerged, which facilitate the production of these

videos.

-Fully enjoying these videos requires an active

profile that can receive suggestions from the platform’s algorithm. Unlike booktubers,

whose videos could be browsed without logging into a Google profile, exploring

a range of booktoks needs an active profile on

the platform. This also allows users to create groups, follow tags, and engage

in comments more directly.

- Although there are also bookinfluencers,

in many cases the book itself is the primary focus of the video, which can be

used in various educational contexts (Rovira-Collado & Ruiz-Bañuls, 2022).

The limitations of this research are acknowledged,

with a specific corpus of videos with characteristics that were primarily

dictated by the platform’s algorithm. Additionally, the inherent bias of the

research team, which sought to identify differences from earlier epitexts, is also acknowledged. More comprehensive

analyses, such as those conducted with booktubers (Tomasena,

2022), could leverage specific APIs to gather macrodata

from these interactions

As a future outlook,

identifying the literary trends promoted by booktoks

is proposed, although it is anticipated that these will largely consist of

current bestsellers in young adult literature. Further research is needed to

confirm the extent to which these videos influence sales across genres (Merga, 2021; Martens et al., 2022). Additionally, specific

analyses of interactions between content creators and their audiences could be

explored (Roig-Vila, Romero-Guerra, & Rovira-Collado, 2021). Comments, live

broadcasts, replies (responses to other videos), duets (videos created by two

people from separate devices), stitches (video overlays), and other forms of

interaction represent areas yet to be examined. Among virtual epitexts, it is the hour of #Booktok.

Authors’

Contributions

Conceptualisation: J.R.-C.,S.M.;

Methodology: J.R.-C., F.A.M.-C.,S.M.; Data curation: F.A.M.-C.,S.M.;

Validation: J.R.-C., F.A.M.-C.,S.M.; Initial draft writing: S.M.; Review and

editing: J.R.-C.,F.A.M.-C.

Funding

This research is part of the Red de Investigación en Docencia Universitaria Narrativas Visuales y Formación

Literaria en Educación Infantil (6216) (University Teaching Research Network:

Visual Narratives and Literary Training in Early Childhood Education) at the

University of Alicante.

References

Abidin, C. (2020). Mapping Internet Celebrity on

TikTok: Exploring Attention Economies and Visibility Labours. Cultural Science

Journal, 12(1), 77–10. https://doi.org/10.5334/csci.140

Allué, C., & Cassany, D.

(2023). Gravando vídeos:

educação literária multimodal. Texto

Livre, 16, p.e41797. https://doi.org/10.1590/1983-3652.2023.41797

Amo, M. del (1964). La hora del cuento. [Versión digital 2004]. https://www.cervantesvirtual.com/obra/la-hora-del-cuento--0/

Aronson, J. (1994). A Pragmatic View of Thematic Analysis. The Qualitative Report, 2, 1-3. https://nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol2/iss1/3/

Blanco Martínez, A., & González Sanmamed, M. (2021). Aprender desde la perspectiva de las

ecologías: una experiencia en Secundaria a través del teatro y de Tiktok. Educatio Siglo XXI, 39(2),

169–190. https://doi.org/10.6018/educatio.465551

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3,

77-101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Caldeiro-Pedreira,

M. C. y Yot-Domínguez, C. (2023). Usos

de TikTok en educación. Revisión sistemática de la aplicabilidad didáctica de

TikTok. Anàlisi: Quaderns de

Comunicació

i Cultur, 69,

53-73. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/analisi.3630

Calvo González, S., & San Fabián

Maroto, J. L. (2018). Selfies, jóvenes y sexualidad

en Instagram: representaciones del yo en formato imagen. Pixel-Bit. Revista De Medios Y Educación, (52), 167–181. https://doi.org/10.12795/pixelbit.2018.i52.12

Cordón-García, J. A., Alonso-Arévalo, J.,

Gómez-Díaz, R., & Linder, D. (2013). Social Reading:

Platforms, Aplications, Clouds and Tags. Chandos Publishing.

Cordón-García, J.

A. & Gómez-Díaz, R. (Eds.) (2019). Lectura, sociedad y redes: colaboración, visibilidad y recomendación en

el ecosistema del libro. Marcial Pons.

DeSantis, L.,

& Ugarriza, D. (2000). The Concept of Theme as Used in Qualitative Nursing Research. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 22,

351-372. https://doi.org/10.1177/019394590002200308

Dezuanni, M., Reddan, B., Rutherford, L., & Schoonens, A. (2022). Selfies and shelfies

on #bookstagram and #booktok – social media and the mediation of Australian

teen reading, Learning, Media and

Technology, 47(3), 355-372. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2022.2068575

Fisher, E. (2022).

Algorithms and subjectivity: The

subversion of critical knowledge. Routledge.

García Rodríguez, A. & Rubio González,

E. (2013). Un paseo por la blogosfera de la literatura infantil y juvenil

española: de los blogs “lijeros” a Facebook. En M. B.

Santana & C. Travieso (Coords.), Puntos de Encuentro. Los primeros 20 años de

la Facultad de Traducción y Documentación de la Universidad de Salamanca (pp.

51-72). Universidad de

Salamanca.

García-Roca, A.

(2020). Spanish Reading Influencers in Goodreads: Participation, Experience and

Canon Proposed. Journal of New Approaches

in Educational Research, 9(2), 153-166. https://doi.org/10.7821/naer.2020.7.453

Guiñez-Cabrera, N., & Mansilla-Obando,

K. (2022). Booktokers: Generar y compartir contenidos

sobre libros a través de TikTok. Comunicar, 71, 119-130. https://doi.org/10.3916/C71-2022-09

Hepp, A. (2020). Deep mediatization. Routledge.

Hernández Heras, L., Muela Bermejo, D.,

& Tabernero Sala, R. (2022). Evaluar el uso de las redes sociales de

lectura en la educación literaria en contextos formales e informales. Diseño y

validación de la herramienta RESOLEC. Pixel-Bit.

Revista de Medios y Educación, 64, 139–164. https://doi.org/10.12795/pixelbit.93831

Hernández-Ortega, J. & Rovira-Collado,

J. (2022). Expansión Social en la Didáctica de la Lengua y la Literatura a

través de Instagram. En S. Gala Pellicer (Ed.) Innovación educativa aplicada a la enseñanza de la lengua (pp.

11-30). Dykinson.

IAB Spain

(2022). Estudio anual redes sociales 2022.

https://iabspain.es/estudio/estudio-de-redes-sociales-2022/

Jerasa, S., & Boffone, T.

(2021). BookTok 101: TikTok, Digital Literacies, and

Out-of-School Reading Practices. Journal

of Adolescent & Adult Literacy,

65(3), 219-226 https://doi.org/10.1002/jaal.1199

Kozinets, R. V. (2021). Netnography today: a call to evolve, embrace, energize, and electrify.

En Robert V. Kozinets, y Rossella C. Gambetti (Eds.), Netnography

unlimited: understanding technoculture using

qualitative social media research (pp. 3-23). Routledge.

Lluch, G., Tabernero-Sala, R., &

Calvo-Valios, V. (2015). Epitextos

virtuales públicos como herramientas para la difusión del libro. Profesional de la información, 24(6),

797-804. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2015.nov.11

Martens, M., Balling,

G., & Higgason, K. A. (2022). #BookTokMadeMeReadIt: young adult reading communities

across an international, sociotechnical landscape. Information and Learning Sciences, 123(11/12), 705-722 https://doi.org/10.1108/ils-07-2022-0086

Merga, M. K. (2021). How can Booktok

on TikTok inform readers' advisory services for young people? Library & Information Science Research,

43(2). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2021.101091

Natarajan, N.

(2024). Do They Stop? How Do They Stop? Why Do They Stop? Whether, How, and Why

Teens Insert “Frictions” Into Social Media’s Infinite Scroll. International

Journal Of Communication, 18, 1956-1975. https://ijoc.org/index.php/ijoc/article/view/21618

Nielsen Book UK

(2021). Examining The Booktok

Potential. https://nielsenbook.co.uk/examining-the-booktok-potential/

Paladines, L. V., & Aliagas, C.

(2021). Booktuber: lectura en red, nuevos

literacidades y aplicaciones didácticas. EDMETIC,

Revista de Educación Mediática y TIC, 10(1), 58-72. https://doi.org/10.21071/edmetic.v10i1.12234

Paladines, L.,

& Aliagas, C. (2023). Literacy and literary

learning on BookTube through the lenses of Latina

BookTubers. Literacy, 57.

17–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/lit.12310

Paladines-Paredes, L. V., & Margallo,

A. M. (2020). Los canales booktuber como espacio de

socialización de prácticas lectoras juveniles. Ocnos. Revista De Estudios Sobre Lectura, 19(1), 55-67. https://doi.org/10.18239/ocnos_2020.19.1.1975

Penguin (2020).

The best TikTok accounts to follow for book lovers. https://www.penguin.co.uk/articles/2020/08/tiktok-booktok-best-accounts-literature-books

Petrillo, S.

(2021). What Makes TikTok so Addictive?: An Analysis

of the Mechanisms Underlying the World’s Latest Social Media Craze. Brown

Undergraduate Journal of Public Health. https://sites.brown.edu/publichealthjournal/2021/12/13/tiktok/

Quiles Cabrera, M. del C. (2020). Textos

poéticos y jóvenes lectores en la era de Internet: de “Booktubers”,

“bookstagrammers” y “followers”.

Contextos Educativos. Revista De

Educación, (25), 9–24. https://doi.org/10.18172/con.4260

Roig-Vila, R., Romero-Guerra, H. &

Rovira-Collado, J. (2021). BookTubers as

Multimodal Reading Influencers: An Analysis of Subscriber Interactions. Multimodal

Technologies and Interaction. 5(7), 39.

https://doi.org/10.3390/mti5070039

Rovira-Collado, J., & Ruiz-Bañuls, M. (2022). BookTok

como nuevo epitexto virtual para la formación lectora

y la competencia digital docente. En D. Ortega-Sánchez y I. M. Gómez Trigueros

(Eds.), Investigación e innovación con TAC en educación mediática: retos,

experiencias y brecha digital en entornos pedagógicos emergentes (pp. 142-151).

Tirant Lo Blanch.

Rovira-Collado, J. (2017). Booktrailer y Booktuber como herramientas LIJ 2.0 para el desarrollo del

hábito lector. Investigaciones Sobre Lectura, (7), 55-72. https://doi.org/10.24310/revistaisl.vi7.10981

Rovira-Collado, J., Martínez-Carratalá,

F.A., & Miras, S. (2024). Booktok: análisis de

las estrategias discursivas multimodales para la promoción de la lectura en

TikTok. Texto Livre.

17 https://doi.org/10.1590/1983-3652.2024.51641

Rovira-Collado, J. Miras, S., &

Martínez-Carratalá, F.A.. (2024). ANEXO DATOS.

Investigación: La hora del booktok: caracterización

de nuevos vídeos para la promoción lectora en el móvil. Zenodo. DOI:

10.5281/zenodo.14507130 https://zenodo.org/records/14507130

Sánchez García, R., & Aparicio Durán,

P. (2020). Los hijos de Instagram. Marketing editorial. Poesía y construcción

de nuevos lectores en la era digital. Contextos

Educativos. Revista de Educación, 0(25), 41-53. https://doi.org/10.18172/con.4265

Sanz-Tejeda, A., Lluch, G. (2024). Temas,

métodos y resultados de investigación sobre TikTok/Instagram y lectura.

Revisión sistemática bibliográfica. Tejuelo, (39), 131-164. https://doi.org/10.17398/1988-8430.39.131

Siles, I., Valerio-Alfaro, L., &

Meléndez-Morán, A. (2022). Learning to like

TikTok and not: Algorithm awareness as process. New Media & Society,

0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448221138973

Sorensen, K.,

& Mara, A. (2014). Booktubers as a Networked Knowledge Community. En M.

Limbu y B. Gurung (Eds.), Emerging

Pedagogies in the Networked knowledge Society: Practices integrating social

media and globalization (pp. 87-99). IGI GLobal.

Talbot, D. (2023).

Impact of Social Media on Book Publishing

Industry. Wordstated. https://wordsrated.com/impact-of-social-media-on-book-publishing-industry/

Tomasena, J. (2019). Negotiating Collaborations: BookTubers,

The Publishing Industry, and YouTube’s Ecosystem. Social Media + Society,

5(4), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305119894004

Tomasena, J.

M. (2021). ¿Quiénes son los bookTubers?:

características de los video-blogueros literarios en lengua española. Ocnos. Revista De Estudios Sobre Lectura, 20(2),

43-55. https://doi.org/10.18239/ocnos_2021.20.2.2466

Tomasena, J.

M. (2022). Los géneros audiovisuales en la producción de los booktubers: un análisis cuantitativo. BiD: textos universitaris de biblioteconomia i documentació,

49. https://doi.org/10.1344/BiD2022.49.02

Turpo Gebera, O.

W., (2008). La netnografía: un método de

investigación en Internet. EDUCAR, 42, 81-93. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=342130831006

Van Dijck, J.

(2013). The culture of connectivity: a critical history of

social media. Oxford

University Press.

Vizcaíno-Verdú, A., Contreras-Pulido, P.,

& Guzmán-Franco, M. D. (2019). Reading and informal learning trends on YouTube: The

booktuber. Comunicar, 59, 95-104. https://doi.org/10.3916/C59-2019-09

Wang, X., &

Guo, Y. (2023). Motivations on TikTok addiction: The moderating role of

algorithm awareness on young people. Profesional

de la información, 32(4). https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2023.jul.11