The utilisation of

the Flipgrid application through mobile devices to enhance motivation and oral

expression skills in secondary school students learning English as a foreign

language

Uso de la aplicación Flipgrid a través de dispositivos móviles para

mejorar la motivación y las habilidades de expresión oral en inglés del

alumnado de la ESO

Dra. Verónica Chust-Pérez.

Profesora asociada.

Universidad de Alicante. España

Dra. Verónica Chust-Pérez.

Profesora asociada.

Universidad de Alicante. España

Dra. Rosa Pilar Esteve-Faubel.

Profesora Titular

de Universidad. Universidad de Alicante. España

Dra. Rosa Pilar Esteve-Faubel.

Profesora Titular

de Universidad. Universidad de Alicante. España

Dra. María del Carmen Fernández-Morante. Profesora Titular de Universidad. Universidad de Santiago

de Compostela. España

Dra. María del Carmen Fernández-Morante. Profesora Titular de Universidad. Universidad de Santiago

de Compostela. España

Dr. José María Esteve-Faubel.

Catedrático de

Universidad. Universidad de Alicante. España

Dr. José María Esteve-Faubel.

Catedrático de

Universidad. Universidad de Alicante. España

Received: 2025/02/02 Revised 2025/02/03 Accepted: 2025/04/02 Online First: 2025/04/09 Published: 2025/05/01

How to cite:

Chust-Pérez, V., Esteve-Faubel,

R.P., Fernández-Morante, Mª. C., & Esteve-Faubel, J.M. (2025). The utilisation of the Flipgrid application

through mobile devices to enhance

motivation and oral expression

skills in secondary school students learning English as a foreign language [Uso de la aplicación Flipgrid

a través de dispositivos móviles para mejorar la motivación y las habilidades

de expresión oral en inglés del alumnado de la ESO]. Pixel-Bit. Revista de Medios y Educación, 73, art.6. https://doi.org/10.12795/pixelbit.113494

ABSTRACT

This exploratory study examines the impact of Flipgrid

and the generative AI tool, Copilot, on the development of oral expression and

motivation among Year 7 students in English language learning. The aim is to

ascertain how these technological tools can enhance fluency, pronunciation, and

confidence when students communicate in a second language. A sequential

explanatory mixed-methods design was employed, combining both quantitative and

qualitative analysis. Pre-tests and post-tests were administered to two groups:

one with technology-mediated learning and the other without. Fluency,

vocabulary, grammar, pronunciation, and levels of anxiety and motivation were

assessed. The data reveals that the group using Flipgrid and Copilot showed

significant improvements in fluency, vocabulary, and grammar, along with

increased motivation and reduced anxiety. However, no notable advances in

pronunciation were observed. The flexible access to

materials and immediate feedback fostered autonomy and collaborative learning. The

study affirms the value of m-learning and digital tools in English language

instruction, highlighting the importance of active methodologies and

well-planned pedagogy to maximise benefits.

Este estudio

exploratorio analiza el impacto de Flipgrid y la IA

generativa Copilot en el desarrollo de la expresión

oral y la motivación en estudiantes de 1º de ESO en el aprendizaje del inglés.

Se busca determinar cómo estas herramientas tecnológicas pueden mejorar la

fluidez, pronunciación y confianza de los alumnos al comunicarse en una segunda

lengua. Se empleó un diseño mixto secuencial explicativo, combinando análisis

cuantitativo y cualitativo. Se aplicaron pretest y postest

a dos grupos: uno con aprendizaje mediado por tecnología y otro sin ella. Se

evaluaron fluidez, vocabulario, gramática, pronunciación y niveles de ansiedad

y motivación. Los datos muestran que el grupo que utilizó Flipgrid

y Copilot experimentó mejoras significativas en

fluidez, vocabulario y gramática, además de una mayor motivación y menor

ansiedad. Sin embargo, no se observaron avances relevantes en pronunciación. El

acceso flexible a materiales y la retroalimentación inmediata favorecieron la

autonomía y el aprendizaje colaborativo. El estudio confirma el valor del m-learning y las herramientas digitales en la enseñanza del

inglés. Se destaca la importancia de metodologías activas y planificación

didáctica adecuada para maximizar beneficios.

KEYWORDS· PALABRAS CLAVES

Habilidades de expresión oral; EFL (inglés

como lengua extranjera); Educación digital; Aprendizaje móvil; Inteligencia

artificial

1. Introduction

Proficiency in at least one language other than one's

mother tongue is now recognised as an essential component of a person's

well-rounded education (Agenda 2030 UNESCO, 2016; Baker & Fang, 2021) and

is considered as one of the key competences for lifelong learning in the

European reference framework (Council of the European Union, 2018).

Communicative competence in any language is developed

through four fundamental skills: listening, reading, writing and speaking, and

among these, oral expression is considered a key indicator of language

proficiency (Hinkel, 2005). However, this skill is not only a communicative

act, but also a significant challenge in the process of learning a second

language.

In the specific context of this study, the focus is on

the acquisition of English as a second language (L2) during compulsory

secondary education [Educación Secundaria Obligatoria (ESO)] given its

relevance as a lingua franca (Crystal, 2003; Jenkins & Leung, 2017) in

academic, scientific, business and technological spheres. During this stage,

which spans from 11 to 16 years of age, particular challenges present

themselves due to the fluctuations in confidence, motivation and anxiety levels

characteristic of adolescent psycho-affective development.

It can therefore be argued that the central issue in

teaching English as L2 in ESO is how teachers should address the specific

difficulties faced by adolescents in developing their oral competence in this

language.

The scientific literature indicates that the

development of oral expression in L2 English during ESO is a significant

challenge in its teaching, because of both the complexity of this skill and the

difficulties faced by teachers.

This ability goes beyond vocabulary and grammar

mastery, as it also requires pragmatic competences, suprasegmental skills and

the ability to communicate effectively in different contexts, including

pronunciation, rhythm and intonation (Agenda 2030 UNESCO, 2016). One of the

main obstacles to its acquisition is a lack of practice in authentic settings due to the fact that, despite the classroom being a

fundamental space for learning, opportunities to develop oral expression in a

spontaneous and meaningful way remain limited.

Furthermore, second language acquisition, especially

in speaking, is influenced by psycho-affective factors such as motivation,

anxiety, fear of making mistakes and lack of confidence, which have an adverse

effect on learners' active participation (Hanifa, 2018; Hinkel, 2005). These

factors may decrease motivation and generate negative attitudes towards oral

communication in English, making it difficult to acquire in the long term

(Dörnyei & Kormos, 2000).

From a pedagogical perspective, teachers face a number of challenges in regard to

the promotion of English speaking. The high ratio of students in the classroom,

with a minimum of 25 per group, hinders the implementation of personalised and

learner-centred oral activities (Arredondo Ruiz, 2017). As a result,

historically, reading and writing have been prioritised over speaking, limiting

students' exposure to real communicative situations in English (Okada et al.,

2018; Tsou, 2005). This lack of interaction in authentic contexts contributes

to anxiety and lack of confidence, reducing learners' motivation to practise

English oral expression (Hanifa, 2018).

To overcome these obstacles, there has been a shift in

recent years towards more communicative approaches and innovative pedagogical

strategies, such as Extramural English. This methodology focuses on encouraging

students to interact in the language outside the classroom, integrating digital

resources that encourage oral practice (Fernández Sesma et al., 2023; Sylvén & Sundqvist, 2012). These tools create

meaningful, safe and motivating learning environments that promote English

interaction in digital environments (Hanifa, 2018; Lyrigkou,

2019).

L2 oral practice can be strengthened through two types

of digital aids: applications designed specifically for language learning and

those that favour social learning, facilitating online communication and

collaboration.

This second group includes the mobile version of the

Flipgrid application, which offers a collaborative and dynamic learning

environment that could be an effective alternative for improving oral

competence in terms of fluency, vocabulary, grammar and pronunciation in

English (Gill-Simmen, 2021; Lowenthal & Moore, 2020).

This approach allows for the integration of social and

academic aspects (Gill-Simmen, 2021; Payne, 2019) and enriches the learning

process inside and outside the classroom, encouraging creativity and promoting

a change of role in students, in line with active teaching strategies. It

should be underlined that Flipgrid is particularly useful for language

learning, as it reinforces not only oral competence but also reading and

writing skills. Our proposed use of Flipgrid responds to the principles of

e-learning 2.0 (Barroso Osuna & Cabero Almenara, 2013; Cabero Almenara,

2006; Cebreiro López et al., 2019) and connectivism (Siemens, 2005).

Flipgrid facilitates synchronous and asynchronous

communication, fostering student motivation and engagement with their learning,

at the same time as connecting social and academic elements (Gill-Simmen, 2021;

Juan-Lázaro & Area-Moreira, 2021). Its use allows students to share videos,

receive feedback and participate in a learning community that combines elements

of social and academic interaction, reducing anxiety and promoting autonomy in

learning to speak (Petersen et al., 2020). It also provides teachers with a

space for formative assessment, interaction with learners and the integration

of formal and informal learning (Godwin-Jones, 2011).

In this context, the incorporation of generative

artificial intelligence tools in the classroom for creating images and visually

representing vocabulary and concepts offers an innovative and motivating

approach for 1st-year ESO students, always being aware of its possible biases

and ethical implications in data collection and protection.

This technology, generative artificial intelligence

combined with Flipgrid, allows students to develop their creativity,

personalise their learning, and can improve understanding of English through

visual experiences and the development of essential digital skills for the

future (Chust-Pérez & Esteve-Faubel, 2022;

Godwin-Jones, 2011; Zhang & Zou, 2022).

However, the effective implementation of these

methodologies requires teachers not only to master linguistic knowledge but

also to have a solid didactic-pedagogical basis (Masuram & Sripada, 2020),

therefore allowing them to design conversational tasks that integrate all the

technical-pedagogical facets for providing students with more meaningful

speaking practice in digital contexts, and themselves with learning assessment

and personalisation tools.

The working hypothesis is that the integration of the

Flipgrid application in educational practice, in combination with generative

artificial intelligence tools, specifically Copilot, has a positive

impact on English L2 oral expression and motivation towards it in 1st-year ESO

students, and the following objectives are proposed to respond to this

hypothesis:

a) To determine the initial level of oral competence

in English of students beginning the 1st year of ESO.

b) To analyse the evolution in essential elements of

oral expression following the implementation of the Flipgrid and Copilot

application in the educational intervention.

c) To evaluate the impact on motivation and anxiety

levels of the use of the Flipgrid and Copilot application through mobile

devices in the oral practice of the English language.

2. Methodology

This study is of an exploratory mixed design type,

implementing a sequential explanatory strategy with a quantitative-qualitative

sequence, starting with a pre and post-test stage of statistical data

collection and analysis followed by a qualitative stage where the experiences

and perceptions of the subjects involved will be explored via the focus group

technique.

The purpose of this methodology is to generate valid

and reliable information that serves as a basis for informed decision-making,

in accordance with contemporary methodological principles in educational

research (Bisquerra Alzina, 2004). In this case, there is an analysis of the

use and contributions of mobile devices and the collaborative and communicative

Flipgrid and generative AI Copilot applications in L2 learning.

For this purpose, a pilot study was carried out in a

Secondary School in the autonomous region of Valencia, where a

technology-mediated teaching activity was implemented to promote the learning

of oral English.

The study used a non-probabilistic purposive sampling

method, selecting two groups of students with homogeneous characteristics

relevant to the research. This approach allowed us to compare the two groups

and explore their experiences within the learning process at the same time.

2.1 Participants

The study was carried out in a secondary school in an

urban area of Alicante (50,000 inhabitants, medium socio-economic level), and

was implemented in two 1st-year ESO groups during the first term, with the

collaboration of the teachers.

Each group comprised 20 students with similar

psycho-pedagogical characteristics, in a lower ratio than in upper years to

facilitate ESO adaptation. The distribution was balanced: experimental group

(GA) 12 boys, 60%; 8 girls, 40% and control group (GB) 11 girls, 55%; 9 boys,

45%.

In GA, since all the pupils had smartphones, oral

expression was worked on Flipgrid and Copilot with mobile devices. In GB, the

same activities were carried out without technology.

2.2 Instruments

Four data collection techniques were implemented: (a)

diagnostic test, (b) play-didactic strategy, (c) confirmatory test and (d)

focus groups.

The diagnostic test used the A1 Movers Cambridge English

Assessment test format. The play-didactic strategy included three Cambridge

English pictures (‘At the doctor's’, ‘From the countryside to the jungle’ and

‘The weather’), each worked on in two sessions as described in Table 1 in order to practice oral production, using Flipgrid and

Copilot with GA and paper with GB. A confirmatory test with the same criteria

was then applied to assess progress in both groups.

Following this test, four focus groups of 10 students

(two per group, balancing gender) were formed to explore perceptions and

emotions about learning. The narratives were analysed in three phases: (1)

keyword identification, (2) categorisation and (3) grouping into

meta-categories.

The analysis, conducted with Atlas.Ti23, showed an

initial agreement of 90% between researchers, reaching 97% after two meetings.

Each student was assigned an acronym according to his or her group (A1, A2,

B1, B2) and gender (Boy - B, Girl - G).

2.3 Pilot study

Following the diagnostic tests, specific activities

were designed for working on oral expression: GA used Flipgrid and Copilot via

mobile devices, while GB did not use technological resources.

The GA students accessed the class on Flipgrid via a

private code, ensuring that only the teacher and peers saw the videos after

validation and feedback.

Teachers organised five heterogeneous groups of four

students, balancing gender, skills and knowledge. The three educational

interventions were developed in these groups throughout the first trimester,

with two sessions per week dedicated to their implementation (Table 1). The

learning activity was the same in both groups, differing only in the format of

the materials and the collaborative environment.

In GA, students used digital materials distributed

online (dictionary, digital images and explanatory video) and combined

face-to-face interaction with Flipgrid, accessed from their mobile devices. For the production of the videos

they relied on some functionalities of the generative AI tool Copilot (help

with image creation).

In GB the materials were printed (paper dictionary,

physical images and teacher's explanation), with all interaction taking place

face-to-face.

Table 1

Study approach (GA-Experimental class group. GB-

Control class group)

|

Stage |

Objective |

Resource |

|

Diagnosis |

Obtain information on initial level of fluency

and accuracy in students' oral expression in English. |

Standardised diagnostic test to be implemented at beginning of

school year. |

|

Implementations |

Oral language practice through group activities concluding with recording of video through Flipgrid in GA

and oral presentation in GB |

Session 1: Teachers provide one of the three

Cambridge English Assessment images mentioned above as starting point for

oral practice: vocabulary, grammatical structures, pronunciation and oral

interaction. GA accesses the image and instruction via Flipgrid on mobile,

while GB receives the image on paper with face-to-face instruction. The lexis

and language structures are worked on collaboratively. GA uses the online

Oxford dictionary and GB uses the printed classroom

dictionary. Each group then describes and interprets the image, structuring

an agreed story. Session 2: GA record their story on video and

share it on Flipgrid; GB present it orally in class. Afterwards, each group

creates a short story with four images, GA using AI (Copilot), and GB using

paper, recreating a communicative situation. GA records and shares the video

on Flipgrid, while GB gives an oral presentation in class. |

|

Evaluation / Verification |

Analyse student progress in English language speaking via

oral communication improvement and willingness to participate. |

End of term test carried out by teachers following

the same parameters as Cambridge English to evaluate student progress. |

3. Analysis and

results

The analysis of the equivalence of the groups in the pretest,

the results of which are shown in Table 2, reveal that the students in both

groups had a similar level at the beginning of the study. As the table shows,

no statistically significant differences were found (p>.05) between the

groups in any of the variables evaluated in the pretest.

Table 2

Difference of

means and statistical significance in pretest

|

|

Levene's test |

Experimental G. |

Control G. |

Statistical Significance |

|||||

|

Dimensions |

F |

p |

M |

SD |

M |

SD |

t |

df |

p |

|

PreA |

.00 |

.97 |

6.20 |

1.64 |

5.45 |

1.64 |

1,447 |

38 |

.156 |

|

PreB |

.11 |

.74 |

5.65 |

1.98 |

4.85 |

1.81 |

1,332 |

38 |

.191 |

|

PreC |

1.63 |

.21 |

4.15 |

2.30 |

3.45 |

1.79 |

1,074 |

38 |

.290 |

|

PreD |

1.31 |

.26 |

3.55 |

2.14 |

2.95 |

1.76 |

.968 |

38 |

.339 |

|

PreTotal |

.00 |

.97 |

6.20 |

1.64 |

5.45 |

1.64 |

1,447 |

38 |

.221 |

The posttest results for the

Experimental and Control groups for each of the dimensions and the total scores

were those shown in Table 2.

Table 3

Means and standard

deviation in posttest

|

|

Experimental Group |

Control Group |

||

|

Dimensions |

M |

SD |

M |

SD |

|

PostA |

7.60 |

1.39 |

6.40 |

1.54 |

|

PostB |

6.60 |

1.88 |

5.50 |

1.82 |

|

PostC |

5.15 |

2.37 |

3.65 |

2.03 |

|

PostD |

4.05 |

2.14 |

3.05 |

1.85 |

|

PostTotal |

23.40 |

7.15 |

18.60 |

6.95 |

A repeated measurements analysis of variance (ANOVA) was

then performed to evaluate the effect of the ‘Intra’ factor and its interaction

with the ‘Between’ factor on the A, B, C, D and Total variables, the results of

which are shown in Table 3.

The analyses revealed a significant main effect of the

‘Intra’ factor on variables A, B, C, and Total (p<.001; Table 4), indicating

that scores in these variables increased, as can be seen when comparing pre-

and post-test scores (Tables 2 and 3) for each variable. However, no

significant effect of the ‘Intra’ factor was found for variable D (p=.154).

After the programme was applied, changes were significantly greater in the

experimental group across all variables (p<.05 in all cases) (Tables 2 and

3). Regarding effect sizes, they were large for the ‘Intra’ variable in A, B,

and Total, moderate for C, and small for D. The effect size for the interaction

between both factors ranged from small to moderate in all variables where the

interaction was significant.

Table 4

Summary of ANOVA of repeated measurements for

variables studied

|

Dimensions |

|

Type III Sum of Squares |

df |

Mean Square |

F |

p-value |

Partial Eta Squared |

|

A |

Intra |

27.61 |

1 |

27.61 |

178.60 |

.000 |

.82 |

|

Intra*Entre |

1.01 |

1 |

1.01 |

6.55 |

.015 |

.15 |

|

|

Error(Intra) |

5.88 |

38 |

.15 |

--- |

--- |

--- |

|

|

B |

Intra |

12.80 |

1 |

12.80 |

129.71 |

0,000 |

.77 |

|

Intra*Entre |

.45 |

1 |

.45 |

4.56 |

0,039 |

.11 |

|

|

Error(Intra) |

3.75 |

38 |

.10 |

--- |

--- |

--- |

|

|

C |

Intra |

7.20 |

1 |

7.20 |

36.00 |

0,000 |

0.49 |

|

Intra*Entre |

3.20 |

1 |

3.20 |

16.00 |

0,000 |

0.30 |

|

|

Error(Intra) |

7.60 |

38 |

0.20 |

--- |

--- |

--- |

|

|

D |

Intra |

1.80 |

1 |

1.80 |

2.12 |

0,154 |

0.05 |

|

Intra*Entre |

0.80 |

1 |

0.80 |

8.94 |

0,005 |

0.19 |

|

|

Error(Intra) |

3.40 |

38 |

0.09 |

--- |

--- |

--- |

|

|

Total |

Intra |

165.31 |

1 |

165.31 |

345.63 |

0,000 |

0.90 |

|

Intra*Entre |

19.01 |

1 |

19.01 |

39.75 |

0,000 |

0.51 |

|

|

Error(Intra) |

18.18 |

38 |

0.48 |

--- |

--- |

--- |

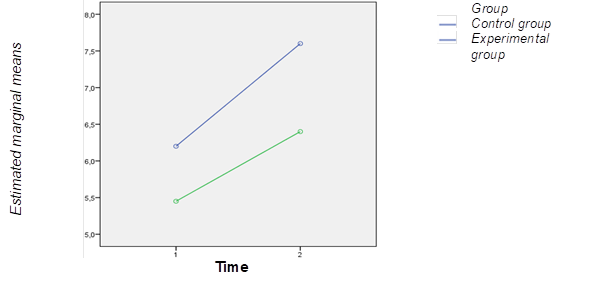

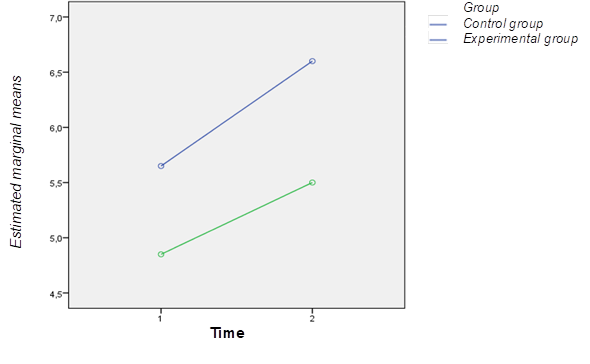

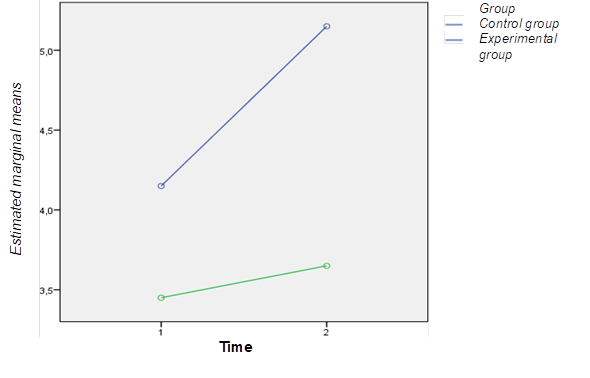

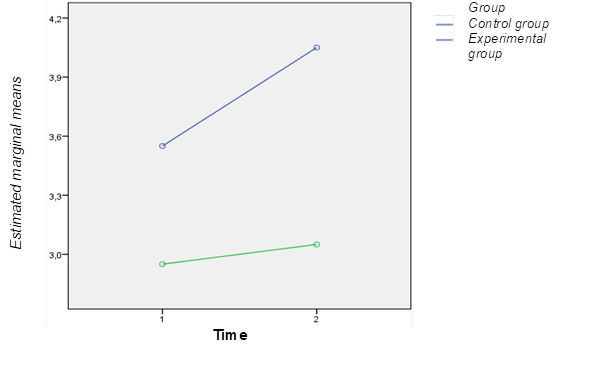

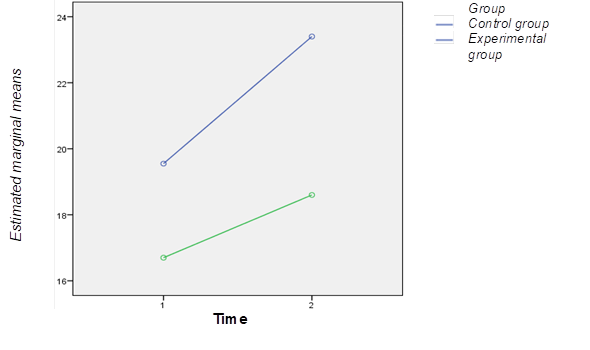

Graphically, all of the above can be clearly observed in the following

figures.

Figure 1

Group

Control group Experimental group Time. Estimated

marginal means for dimension A

Source: own elaboration

Figure 2

Estimated marginal means for dimension B

Source: own elaboration

Figure 3

Estimated marginal means for dimension C

Source: own elaboration

Figure 4

Estimated marginal

means for dimension D

Source: own elaboration

Figure 5

Estimated marginal means for Total dimension

Source: own elaboration

The difference between the two groups in these three

aspects is reflected in their progress rates. GA shows significant improvement

in motivation and reduced anxiety, which positively influences their

willingness to communicate. In contrast, GB shows minimal progress in reducing

foreign language anxiety and motivation, resulting in a low willingness to

communicate.

These results confirm the initial hypothesis about the

positive impact of virtual collaborative tools and environments on oral

expression and motivation to communicate in English.

Regarding performance levels, the degree of

acquisition in each area of oral competence was measured at three levels:

advanced, intermediate, and basic (Table 5). Additionally, teachers provided

each student with detailed feedback, highlighting both improved aspects and

those requiring further development.

Table 5

Results of the practical sessions

|

|

|

Practice 1 |

Practice 2 |

Practice 3 |

|||||||||

|

|

|

GA n=20 |

GB n=20 |

GA n=20 |

GB n=20 |

GA n=20 |

GB n=20 |

||||||

|

|

|

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

|

Fluency |

Advanced |

3 |

15 |

2 |

10 |

3 |

15 |

6 |

30 |

7 |

35 |

8 |

40 |

|

Intermediate |

10 |

50 |

10 |

50 |

10 |

50 |

10 |

50 |

10 |

50 |

11 |

55 |

|

|

Basic |

7 |

35 |

8 |

40 |

7 |

35 |

4 |

20 |

3 |

15 |

1 |

5 |

|

|

Vocabulary |

Advanced |

4 |

20 |

5 |

50 |

10 |

50 |

9 |

45 |

16 |

80 |

15 |

75 |

|

Intermediate |

13 |

65 |

14 |

70 |

11 |

55 |

10 |

50 |

3 |

15 |

4 |

20 |

|

|

Basic |

2 |

10 |

1 |

5 |

1 |

5 |

1 |

5 |

1 |

5 |

1 |

5 |

|

|

Grammar |

Advanced |

3 |

15 |

4 |

20 |

6 |

30 |

7 |

35 |

12 |

60 |

12 |

60 |

|

Intermediate |

12 |

60 |

13 |

65 |

11 |

55 |

11 |

55 |

8 |

40 |

9 |

45 |

|

|

Basic |

5 |

25 |

4 |

20 |

3 |

15 |

2 |

10 |

1 |

5 |

1 |

5 |

|

|

Pronunciation |

Advanced |

3 |

15 |

4 |

20 |

4 |

20 |

6 |

30 |

9 |

45 |

8 |

40 |

|

Intermediate |

10 |

50 |

10 |

50 |

11 |

55 |

14 |

70 |

10 |

50 |

10 |

50 |

|

|

Basic |

6 |

30 |

7 |

35 |

5 |

25 |

2 |

10 |

1 |

5 |

2 |

10 |

|

The results of the three educational interventions

(practices) conducted during the first term reflect faster progress in GA

compared to GB. In GA, the use of Flipgrid extends the physical classroom and

facilitates collaboration and interaction with the teacher in a flexible

virtual environment. Additionally, it incorporates a playful, gamified and

creative dimension that fosters greater student engagement, promoting active

roles such as creator, evaluator (providing feedback), and researcher, thus

enhancing their learning and participation.

Progress was evaluated by comparing the final

assessment results in both groups, analysing student productions (videos on

Flipgrid and in-class performances), as well as observing and assessing their

oral interventions in different contexts: in a cooperative group, in the

general class group, and in interaction with the teacher.

The difference in progress between the two groups is

evident from the first educational intervention. Although faster progress is

observed in GA across all evaluated aspects of oral skills, the greatest

difference lies in fluency and pronunciation. The use of Flipgrid in GA

facilitates faster and greater progress to the advanced level in these aspects

compared to GB.

In Practice 3, over 50% of students using Flipgrid

achieved an intermediate or advanced level in all four evaluated areas of oral

expression. However, although GB also shows progress, the number of students

reaching an advanced level is lower than in GA. This difference is particularly

significant in the final test (Table 3), where significant progress is observed

in all four evaluated areas.

The results also reflect increased motivation and

reduced anxiety in GA thanks to the use of Flipgrid via mobile devices (Table

6). The application allows for detailed monitoring of student work, including

time and frequency of connections, with an increase in oral practice outside

the classroom being observed. As of the first practical, 50% of GA students

connected regularly and for extended periods to create and view their peers'

videos.

Table 6

Improvement in motivation and anxiety in Group A

|

|

|

n=20 |

% |

|

Practice 1 |

Frequent

and extensive connections to Flipgrid outside the classroom. |

10 |

50 |

|

Final video

interventions exceeding one minute. |

6 |

30 |

|

|

Peer

feedback videos exceeding one minute. |

6 |

30 |

|

|

Practice 2 |

Frequent

and extensive connections to Flipgrid outside the classroom. |

14 |

70 |

|

Final video

interventions exceeding one minute. |

12 |

60 |

|

|

Peer

feedback videos exceeding one minute. |

10 |

50 |

|

|

Practice 3 |

Frequent

and extensive connections to Flipgrid outside the classroom. |

20 |

100 |

|

Final video

interventions exceeding one minute. |

17 |

85 |

|

|

Peer

feedback videos exceeding one minute. |

18 |

90 |

The progress between Practice 1 and Practice 3 shows considerable

evolution, suggesting that mobile use has increased motivation and reduced

anxiety about making mistakes. 100% of students connected to Flipgrid outside

the classroom to continue speaking practice, and peer feedback videos exceeding

one minute reflect the cohesion achieved in the class group.

Regarding focus groups, the results show no intragroup

differences, with three main metacodes emerging:

language learning anxiety, motivation, and willingness to communicate (Table

7). The difference between the two groups lies in their progress rates, with GA

showing more notable advances in motivation and reduced anxiety thanks to the

use of Flipgrid in and outside class, which improves their willingness to

communicate. Conversely, GB shows minimal progress in anxiety and motivation

due to the lack of digital tools, resulting in a low willingness to

communicate.

Table 7

Metacodes, codes, and exemplary quotes

|

|

|

Code |

Exemplary quotes |

N=20 |

% |

|

|

Metacode |

Anxiety |

Reducing nerves before speaking. |

“Flipgrid's easy; it’s like TikTok.”(GFA1B) |

18 |

90 |

GA |

|

“I like making videos with Flipgrid and laughing

making them.”(GFA2G) |

17 |

85 |

||||

|

Reducing fear of understanding oral messages |

“I like doing activities like this with my group.”(GFB2B) |

15 |

75 |

|||

|

“I can understand more words from my classmates

and the teacher.”(GFA1G) |

17 |

85 |

||||

|

Motivation |

Enthusiasm in the classroom |

“It’s cool using mobiles to make videos and

images.”(GFA1B) |

20 |

100 |

||

|

“We all brought costumes and things for the

videos.”(GFB2G) |

18 |

90 |

||||

|

Interest outside the classroom |

“We repeated what we had to say at home because

we wanted Likes.”(GFA1G) |

17 |

85 |

|||

|

“I loved using videos to comment on others’ work

in class and at home”(GFA1B) |

20 |

100 |

||||

|

Willingness to communicate |

Work group |

“It was fun listening to my group mates speaking

English.” (GFA1B) |

16 |

80 |

||

|

“We liked learning new words and using them to

describe images.”(GFA1G) |

16 |

80 |

||||

|

General class group |

“It’s really easy to watch and reply with

another video.” (GFA2B) |

20 |

100 |

|||

|

“I had a great time recording videos at home. I

laughed a lot.”(GFA1G) |

18 |

90 |

||||

|

Anxiety |

Reducing nerves before speaking. |

“I spoke in English with my group mates without

feeling nervous.” (GFB2G) |

9 |

45 |

GB |

|

|

“We laughed a lot when we couldn't say a new

word properly.”(GFB1B) |

10 |

50 |

||||

|

Reducing fear of understanding oral messages |

“I can understand the teacher’s instructions

better.”(GFB1G) |

10 |

50 |

|||

|

“I can easily understand what my classmates are

saying.”(GFB2G) |

8 |

40 |

||||

|

Motivation |

Enthusiasm in the classroom |

“I really wanted to act.”(GFB1B) |

8 |

40 |

||

|

“I really enjoyed preparing the decoration for

us to be the best.”(GFB2G) |

7 |

35 |

||||

|

Interest outside the classroom |

“We met at my house to do the story.”(GFB1B) |

9 |

45 |

|||

|

“We all looked for stuff in magazines, stickers

and images for the work.”(GFB2G) |

8 |

40 |

||||

|

Willingness to communicate |

Work group |

“I spoke loads of English in these classes. It

was cool”(GFB2G) |

5 |

25 |

||

|

“We put the learnt words in the work”.(GFB1B) |

6 |

30 |

||||

|

General class group |

“We laughed a lot when we didn't say something

correctly doing the story”.(GFB1G) |

6 |

30 |

|||

|

“I’ve never spoken so much English in my life.”(GFB2B) |

7 |

35 |

4. Discussion

This exploratory study, with a

sequential explanatory mixed design, investigated the impact of integrating the

collaborative virtual environment Flipgrid and the generative AI tool Copilot

for image creation on the development of oral expression and motivation towards

this skill in 1st-year ESO (compulsory secondary education) students. The

results confirm that the educational intervention supported by Flipgrid,

complemented with AI, had a positive impact on oral expression and motivation

towards learning English as a second language. The quantitative and qualitative

data show progress in the oral production of the student group whose learning

was mediated by technology, as well as higher motivation and lower anxiety in

oral participation, compared to the group whose learning was not mediated by

technology.

Regarding the first objective,

the pre-test applied to both groups revealed significant homogeneity in oral competence

levels at the start of the intervention in fluency, vocabulary, grammar, and

pronunciation, allowing the subsequent differences to be attributed to the

effect of the Flipgrid and Copilot tools rather than pre-existing differences.

The initial results align with Cohen’s (2012) study, which identified

difficulties in fluency and pronunciation associated with the articulation of

phonemes and prosodic, paralinguistic and extralinguistic elements. Despite

these difficulties, students demonstrated basic mastery of vocabulary and

grammar, enabling them to construct messages.

The analysis of the posttest,

the second objective, showed that the group whose learning was

technology-mediated experienced significant improvement in fluency, vocabulary,

and grammar, with this improvement being greater than that of the

non-technology-mediated group. This suggests that Flipgrid provided a friendly

and secure collaborative virtual space to practice oral expression (Hanifa,

2018; Lyrigkou, 2019), fostering experimentation with

the language and repetitive, deliberate and contextualised

practice, essential for developing L2 oral competence (Gill-Simmen, 2021;

Lowenthal & Moore, 2020). During the first term, the technology-mediated

group progressed rapidly in fluency and pronunciation, with the majority

reaching an intermediate or advanced level in all four dimensions of oral

expression, while progress for the non-technology-mediated group was less

pronounced. Flipgrid facilitated more effective and

efficient oral practice. However, the post-test showed no significant

improvement in pronunciation, suggesting the need for other specific

ICT-mediated pedagogical strategies for this skill.

The analysis of the third

objective revealed that both groups shared metacodes

related to anxiety and willingness to communicate. Despite this, the

technology-mediated group showed greater predisposition towards oral

interaction, lower anxiety, and higher motivation for learning, both inside and

outside the classroom. These results align with research highlighting the

importance of psycho-affective factors in second language learning (Hinkel,

2005).

The creation of dynamic,

collaborative, and technology-enriched learning environments promoted

continuous and flexible learning, reducing anxiety and increasing motivation

and communicative skills (Gill-Simmen, 2021; Payne, 2019). Students valued the

use of mobile devices and tools like Flipgrid, while the generative AI tool,

via the provision of ideas and immediate feedback, enhanced their autonomy and

turned them into active agents of their learning, improving their motivation.

In contrast, the group whose learning was not mediated by technology showed

lower motivation and less reduction in anxiety.

The introduction of playful

elements in interactions with mobile devices and the use of Flipgrid and

Copilot generated motivation, fostered interest, and reduced anxiety (Dashtestani, 2016; Fombona Cadavieco & Rodil Pérez,

2018). By perceiving it as a game,

students found the activity intrinsically motivating (Chust-Pérez

& Esteve-Faubel, 2022).

The results confirm that

m-learning is a valuable resource in education (El-Hussein & Cronje, 2010; Fallahkhair et al., 2007), encouraging autonomy and

bridging the classroom with adolescent reality. Additionally, it transforms

attitudes towards learning by offering flexible access to materials and

interactive feedback (Milrad & Jackson, 2008;

Stockwell, 2010). When used with appropriate methodology and under teacher

supervision, mobile devices can be important tools for innovating teaching and

expanding learning scenarios by connecting with reality.

This study also showed an

increase in time spent on videos outside the classroom and in app usage, which favours oral practice (Hwang et al., 2016). Moreover,

audiovisual feedback enhances comprehension, cooperation, and critical

thinking. In this regard, Flipgrid facilitates collaborative learning, reduces

errors and strengthens motivation, provided it is integrated with proper

didactic planning. Thus, the use of mobile devices, along with tools like

Flipgrid and Copilot, has not only reinforced English learning but also

stimulated student creativity and teamwork.

5. Conclusions

The study confirms that the

use of mobile devices (m-learning) and collaborative, communicative, and

generative AI applications, within a well-structured teaching proposal,

improves oral expression and motivation in 1st-year ESO students learning

English as a second language. This approach fosters autonomy, connects the

classroom with adolescent reality, and extends oral practice outside the

classroom thanks to flexible access to materials and constant feedback.

Applications and audiovisual

feedback not only strengthen comprehension and critical thinking but also,

through collaborative tools like Flipgrid, promote group learning, reduce

errors, and reinforce motivation. To maximise these

benefits, it is essential for teachers to implement active methodologies and

integrate technology in a structured and meaningful way.

However, the study has

limitations related to the sample, which may hinder the generalisation

of the conclusions obtained to very different

educational contexts. A longitudinal follow-up of participants is not possible,

either, as the organisational dynamics of secondary

schools involve regrouping students when they move up to the 2nd year of ESO,

preventing the evaluation of the persistence or evolution of the intervention’s

effects in the medium or long term.

Although the study

demonstrates improvements in oral expression, it is important to note the

absence of significant progress in student pronunciation. This does not

invalidate the intervention but serves as an indicator of the need to research

and develop more specific and effective pedagogical approaches for teaching

English phonetics and phonology.

To this end, it is necessary to design and validate focused didactic strategies,

including those supported by ICT to offer adaptive

practice or individualised feedback. Exploring the generalisation of these results and their long-term impact

is crucial, taking advantage of the potential of m-learning to stimulate

creativity, flexibility, and teamwork.

Finally, to improve

pronunciation, the systematic use of minimal pairs should be considered,

facilitating auditory discrimination and the production of sounds particularly

challenging for Spanish speakers, such as the distinction between /ɪ/ and

/iː/. Furthermore, structured exercises in

active listening and guided repetition such as songs, short poems and rhymes

should be implemented to help students internalise

the intonation patterns and rhythm characteristic of the English language.

Constructive feedback should also be ensured to address phonemes absent in

Spanish such as /θ/, /ð/ and the aspirated /h/, through explicit and playful introduction

via phonetic games or motivating activities.

Author

contributions

Conceptualisation,

V.Ch.-P., J.M.E.-F.; Data curation, R.P.E.-F., M.C.F.-M.; Formal analysis,

V.Ch.-P., R.P.E.-F., M.C.F.-M., J.M.E.-F.; Investigation, V.Ch.-P.;

Methodology, V.Ch.-P., R.P.E.-F., M.C.F.-M., J.M.E.-F.; Project administration,

J.M.E.-F.; Resources, R.P.E.-F., M.C.F.-M.; Supervision, M.C.F.-M., J.M.E.-F.;

Validation, V.Ch.-P., R.P.E.-F.; Visualisation, M.C.F.-M., J.M.E.-F.;

Writing—original draft, V.Ch.-P., R.P.E.-F., M.C.F.-M., J.M.E.-F.;

Writing—review and editing, V.Ch.-P., R.P.E.-F., J.M.E.-F., M.C.F.-M.

Funding

This research has not

received external funding

Data Availability

Statement

The data set used in this study is available at reasonable request to the

corresponding author

Ethics approval

Not aplicable

Consent for publication

The author has consented to the publication of the results obtained by

means of the corresponding consent forms

Conflicts of interest

The author declares that they have no conflict of interest

Derechos y permisos

Open Access. This article is licensed under

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing,

adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as

you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a

link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if

changes were made.

References

Agenda 2030 UNESCO. (2016). Incheon declaration and Framework for action for the implementation of

Sustainable Development Goal 4. Towards inclusive and equitable quality

education and lifelong learning opportunities for all. Education 2030.

UNESCO. Retrieved 25 February 2023 from https://goo.su/XAY1eD

Arredondo Ruiz, C. (2017). Análisis de las concepciones del

profesorado de Educación Secundaria Obligatoria y Bachillerato sobre la

Didáctica de la Lengua oral: estudio de caso. Revista de Educación de la Universidad de Granada, 24, 81-97.

Baker, W., & Fang, F. (2021). ‘So maybe I’m a global citizen’: developing

intercultural citizenship in English medium education. Language,

Culture and Curriculum, 34(1),

1-17. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2020.1748045

Barroso Osuna, J. M., &

Cabero Almenara, J. (2013). Replanteando el e-learning: hacia el e-learning

2.0. Campus Virtuales, 2(2), 76-87.

Bisquerra Alzina, R. (Ed.). (2004). Metodología de la investigación educativa. Muralla.

Cabero Almenara, J. (2006).

Bases pedagógicas del e-learning. RUSC, Universities & Knowledge Society, 3(1).

https://goo.su/ufEpY

Cebreiro López. B.. Fernández Morante. M. d. C..

& Casal Otero. L. (2019). Tecnologías emergentes y metodologías didácticas:

dos ejes básicos para el éxito educativo. In M. A. Santos Rego. A. Valle Arias.

& M. d. M. Lorenzo Moledo (Eds.). Éxito educativo: claves de

construcción y desarrollo (pp. 173-196). Tirant Humanidades.

Chust-Pérez. V. & Esteve-Faubel.

R. P. (2022). Las canciones como apoyo

didáctico para la enseñanza del inglés en la ESO. In C. Gonzálvez

Macià. R. Sanmartín López. & M. Vicent Juan (Eds.). Nuevos retos

educativos e investigación interdisciplinaria (pp. 77-93). Aula

Magna/McGraw-Hill Interamericana de España.

Cohen, A. D. (2012). Comprehensible Pragmatics: Where

Input and Output Come Together. In M. Pawlak (Ed.), New perspectives on individual differences in language learning and

teaching (pp. 249-261). Springer

Berlin Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-20850-8_16

Consejo de la Unión Europea.

(2018). Recomendación del Consejo, de 22

de mayo de 2018, relativa a las competencias clave para el aprendizaje

permanente (Texto pertinente a efectos del EEE.). Bruselas: Unión Europea

Retrieved from https://goo.su/6YpUZMD

Crystal, D. (2003). English as a global language. Cambridge University Press.

Dashtestani, R. (2016). Moving bravely towards mobile

learning: Iranian students' use of mobile devices for learning English as a

foreign language. Computer Assisted

Language Learning, 29(4),

815-832. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2015.1069360

Dörnyei, Z., & Kormos, J. (2000). The role of

individual and social variables in oral task performance. Language Teaching Research, 4(3),

275-300. https://doi.org/10.1177/136216880000400305

El-Hussein, M. O. M., & Cronje, J. C. (2010).

Defining Mobile Learning in the Higher Education Landscape. Educational Technology & Society, 13(3), 12-21. http://www.jstor.org/stable/jeductechsoci.13.3.12

Fallahkhair, S., Pemberton,

L., & Griffiths, R. (2007). Development of a cross‐platform ubiquitous language learning service via

mobile phone and interactive television. Journal

of computer assisted Learning, 23(4),

312-325. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2729.2007.00236.x

Fernández Sesma, M. G., Alvarez Flores, E. P., &

Reyes Arias, K. (2023). Enseñanza

del idioma inglés en educación primaria: Fortalecimiento de vocabulario y

pronunciación a través de podcast. Pixel-Bit. Revista de

Medios y Educación, 68, 245-272. https://doi.org/10.12795/pixelbit.100107

Fombona Cadavieco,

J., & Rodil Pérez, F. J. (2018). Niveles de uso y aceptación de los

dispositivos móviles en el aula. Pixel-Bit: Revista de

medios y educación, 52, 21-35.

https://doi.org/10.12795/pixelbit.2018.i52.02

Gill-Simmen, L. (2021). Using Padlet in instructional

design to promote cognitive engagement: a case study of undergraduate marketing

students. Journal of Learning Development

in Higher Education, (20). https://doi.org/10.47408/jldhe.vi20.575

Godwin-Jones, R. (2011). Emerging technologies: Mobile

apps for language learning. Language

Learning & Technology, 15(2),

2-11. https://doi.org/10125/44244

Hanifa, R. (2018). Factors generating anxiety when

learning EFL speaking skills. Studies in

English Language and Education, 5(2),

230-239. https://doi.org/10.24815/siele.v5i2.10932

Hinkel, E. (Ed.). (2005). Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning (Vol.

III). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315716893

Hwang, W.-Y., Shih, T. K., Ma, Z.-H., Shadiev, R., & Chen, S.-Y. (2016). Evaluating listening

and speaking skills in a mobile game-based learning environment with

situational contexts. Computer Assisted

Language Learning, 29(4),

639-657. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2015.1016438

Jenkins, J., & Leung, C. (2017). Assessing English

as a Lingua Franca. In E. Shohamy, I. G. Or, & S.

May (Eds.), Language Testing and

Assessment (pp. 103-117). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-02261-1_7

Juan-Lázaro, O., & Area-Moreira, M. (2021). Gamificación superficial en e-learning:

evidencias sobre motivación y autorregulación. Pixel-Bit. Revista de Medios y Educación, 62, 146-181. https://doi.org/10.12795/pixelbit.82427

Lowenthal, P. R., & Moore, R. L. (2020). Exploring

student perceptions of Flipgrid in online courses. Online Learning Journal, 24(4),

28-41. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v24i4.2335

Lyrigkou, C. (2019). Not

to be overlooked: agency in informal language contact. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 13(3), 237-252. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2018.1433182

Masuram, J., & Sripada, P. N. (2020). Developing

Speaking Skills Through Task-Based Materials. Procedia Computer Science,

172, 60-65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2020.05.009

Milrad, M., & Jackson, M. H. (2008). Designing and

implementing educational mobile services in university classrooms using smart

phones and cellular networks. International

Journal of Engineering Education, 24(1),

84-91.

Okada, Y., Sawaumi, T., & Ito, T. (2018). How do

speech model proficiency and viewing order affect Japanese EFL learners’

speaking performances. Computer Assisted

Language Learning Electronic Journal,

19(2), 61-81. http://callej.org/journal/19-2.html

Payne, L. (2019). Student engagement: three models for

its investigation. Journal of Further and

Higher Education, 43(5), 641-657.

https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2017.1391186

Petersen, J. B., Townsend, S. D., & Onak, N.

(2020). Utilizing Flipgrid Application on Student Smartphones in a Small-Scale

ESL Study. English Language Teaching, 13(5), 164-176. https://doi.org/

10.5539/elt.v13n5p164

Siemens, G. (2005). Connectivism: A learning theory

for the digital age. International

Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 2(1), 3-10. Retrieved January 10, 2024,

from https://goo.su/aQMMDd

Stockwell, G. (2010). Using mobile phones for

vocabulary activities: Examining the effect of platform. Language Learning & Technologvy, 14(2), 95-110.

Sylvén, L. K., & Sundqvist, P. (2012). Gaming as

extramural English L2 learning and L2 proficiency among young learners. ReCALL, 24(3), 302-321. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095834401200016X

Tsou, W. (2005). Improving speaking skills through

instruction in oral classroom participation. Foreign Language Annals, 38(1),

46-55. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.2005.tb02452.x

Zhang, R., & Zou, D. (2022). Types, purposes, and

effectiveness of state-of-the-art technologies for second and foreign language

learning. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 35(4), 696-742. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2020.1744666