App for measuring early childhood development:

a case study

App para la medición del desarrollo

temprano infantil: estudio de caso

Dra. Olga

María Alegre de la Rosa. Catedrática de

Universidad. Universidad de la Laguna. España

Dra. Olga

María Alegre de la Rosa. Catedrática de

Universidad. Universidad de la Laguna. España

Dr. Luis Miguel Villar Angulo. Catedrático de Universidad. Senior. Universidad de Sevilla. España

Dr. Luis Miguel Villar Angulo. Catedrático de Universidad. Senior. Universidad de Sevilla. España

Received: 2025/02/02 Revised 2025/02/19 Accepted: 2025/04/02 Online First: 2025/04/12 Published: 2025/05/01

How

to cite:

Alegre de la Rosa, O. M.,

& Villar-Angulo, L. M. (2025). App para la medición del desarrollo temprano

infantil: estudio de caso [Technological application for measuring early

childhood development: case study]. Pixel-Bit. Revista

De Medios Y Educación, 73, art.7. https://doi.org/10.12795/pixelbit.114160

ABSTRACT

Introduction. Integrating smartphone use into an

emerging early childhood education curriculum can offer several significant

benefits.

Methodology. We apply mixed methods (evidence-based

practices, action research, formative evaluation, and integration of

technological devices).

Results. A manual has been created that summarizes early

intervention practices that improve child development outcomes. An Open

Educational Resource (OER) has incorporated child development assessment tools

and intervention exercises for children. An app has facilitated access to OER.

Finally, the app's perceptions used by families and practitioners

(professionals) aged 0-5 years have been measured through the User Experience

Questionnaire (CEU).

Discussion. The evaluative findings indicated that the

age of family members and practitioners made a powerful difference in the

educational app's attractiveness, efficiency, and stimulation. In contrast, academic qualification only affected

controllability

RESUMEN

Introducción. La integración

del uso de teléfonos inteligentes en un currículo emergente de educación

infantil puede ofrecer una serie de beneficios significativos.

Metodología. Se han aplicado

métodos mixtos (prácticas basadas en la evidencia, investigación-acción,

evaluación formativa e integración de dispositivos tecnológicos).

Resultados. Se ha creado un

manual que resume prácticas de intervención temprana que mejoran los resultados

del desarrollo infantil. Se han incorporado instrumentos de evaluación del

desarrollo infantil y ejercicios de intervención para niños en un Recurso

Educativo Abierto (REA). Se ha implantado una app

educativa para facilitar el acceso a REA. Finalmente, se han medido las

percepciones de familiares y practicadores profesionales sobre(profesionales)

de la app educativa usada para el desarrollo infantil

entre 0 y 5 años a través del Cuestionario Experiencia de Uso (CEU).

Discusión. Los hallazgos

evaluativos indicaron que la edad de los miembros de las familias y los

profesionales familiares y practicadores (profesionales) marcaba una diferencia

potente en la atracción, eficiencia y estimulación de la app

educativa, mientras que la titulación académica solo lo hacía en la dimensión

controlabilidad.

.

KEYWORDS· PALABRAS CLAVES

Early childhood development, smartphone, educational applications, technology platforms, web

design.

Desarrollo temprano infantil, teléfono

inteligente, aplicaciones educativas, plataformas tecnológicas, diseño web.

1. Introduction

Smartphones have benefits in

an emerging early childhood education curriculum because they allow access to

educational content to develop reading, writing, numeracy and problem solving.

The applications included in smartphones adjust the difficulties of educational

tasks according to children's progress. Simultaneously, they foster parents'

digital literacy by enabling active and participatory learning, while giving

immediate feedback to children and parents on children's mistakes.

1.1. Key factors and

applications related to the use of technology in childhood

The factors that influence the

use of digital technology can be of different nature: individual (such as age, cognitive

development or personal interests), family (and in this case we find parental

beliefs, homework supervision or the rules established at home), educational (and thus we find the availability of resources,

school policies or teacher training). Finally, socioeconomic factors (including

access to devices and level of internet connectivity) (Blackwell et al., 2014;

Collier-Meeket al., 2020).

The abundance of studies around associations between

screen time, emotional development, social skills, and sleep quality has

prompted a meta-analysis of the efficiency of technologies related to

psychosocial factors in child development (Mallawaarachchi et al., 2022).

Following the analyses, the authors discussed that “increased early childhood smart-phone and tablet use was correlated, albeit weakly,

with poorer overall child-specific developmental factors (i.e., aggregate of

psychosocial, cognitive and sleep domains” (p. 27).

Technological platforms are

used in early childhood education to improve children's language, social and

motor skills, to document the activities they perform and to adapt the

curriculum to their present needs (Parnell & Bartlett, 2012). Ultimately, the

use of technologies understood as narrative games or problem-solving platforms

for school content serves to teach social-emotional skills, fundamentally for

those children who lack adequate social-emotional learning (Nikolopoulou &

Gialamas, 2015; McClelland et al., 2017). Consequently, it seems recurrent to

imbue beliefs in faculty to design learning experiences based on digital games

(Odom & Wolery, 2003).

Some authors perceive games as

motivational and educational tools; others doubt their pedagogical

effectiveness (McClelland, Tominey, Schmitt, & Duncan, 2017). The use of

technologies such as narrative games or problem-solving platforms for school content

serves to teach social-emotional skills, primarily for those children who lack

social-emotional learning, because qualitative studies have indicated that

technology had a positive effect on engagement, social interactions, and

mathematical skills (Zomer & Kay, 2016). Simultaneously, increased

communication between parents and educators through interactive platforms is

considered transcendental.

In this sense, programs aimed

at children with special needs (e.g., augmentative communication) have been

implemented and are summarized in the monographic issue of the International

Journal of Special Education, 34(1), 2019. Likewise, interventions with

technologies to teach older children have been evaluated with programs such as

augmented reality or gamification that have shown positive results in

motivation and learning, and self-assessment has been promoted in older

children through the use of digital tools (Hudson,

2019). Likewise, the need to measure the long-term effects for the

generalization of knowledge in an emerging curriculum has been noticed (Lim,

2017).

A correlation has been found

between parents' educational self-efficacy and enhanced use of technologies at

home (Hadlingtonet al., 2019; Fidan & Olur, 2023). Moreover, in 2023, Fidan

and Olur discussed “studies especially on the effects and roles of digital

parenting” (p. 15192), which use technologies to teach parenting skills for

effective parenting, e.g., video tutorials or apps that provide feedback on

parenting strategies. Convincingly, joint use of devices between parents and

children fosters emotional connection and enhances children's learning.

However, excessive use of

technological devices is related to aggressive moods, impulsivity

and lower self-regulation of users. Therefore, interventions based on media

education can reduce disruptive behaviors. An appropriate use of technologies

by children has the benefit of promoting interactive learning and the

development of digital skills. On the contrary, the psychological risks of

misuse of technologies refer to attention problems, social isolation and

technological dependence. However, technological applications contribute to the

sensory and motor development of children with disabilities (Pila et al.,

2021).

Haptic technologies that allow

users to interact with the environment by tactile means have social uses in

socio-educational simulations and research and in physical therapies. In this

regard, technological tools such as digital questionnaires have been developed

to assess the cognitive, motor, social, and emotional development of young

children and monitor their developmental milestones (Louisiana Department of

Education, 2023). Among the data

collected by the questionnaires are academic progress and social skills to

customize interventions based on the findings, always taking care of the

ethical principles of confidentiality in handling sensitive data within

educational settings (Lohmann et al., 2024). Documentation of learning with

digital tools is unquestionable to record children's progress in real time

(e.g., digital portfolios) (Mertala, 2019).

With this in mind, smartphones have become an administrative and documentary tool (Goh et al., 2015).

The use of these devices in schools allows tracking children's learning

progress, communicating with parents and recording daily academic activities

(Sørenssen & Bergschöld, 2021). Consequently, digital tools connect

families to intervention resources (Dunst et al., 2019; Dunst et al., 2020).

Indeed, some purpose-designed mobile apps can detect early signs of

developmental delays in children (Wallace, 2018).

The opinions of teachers and

developers of smart technologies used by children are complementary. Precisely,

teachers reason that technologies are additional to children's development,

stressing the importance of adequate supervision (Vidal-Hall et al., 2020),

while developers seek a balance between entertainment and an education in

application design (Kucirkova & Flewitt, 2020; Kucirkova et al., 2021). In

both cases, the need to empirically validate new tools before their widespread

implementation seems evident.

To this end, it is pertinent

to integrate learning theories (constructivism, sociocultural) in the design

and evaluation of educational technologies. Likewise, the establishment of

clear parental rules and regulations on children's time in front of a screen,

type of content and schedules of use of technologies, which should be flexible

and adapted to the individual needs of each child, is also timely (Merdin &

Şahinb, 2023; Griffith et al., 2024). The research by Bonilla and Aguaded

(2018) manifested the interest shown by families to the proposal of receiving

training in information and communication technology at school, i.e., parents

demand participation in training activities to improve their digital and media

skills. Consequently, parents' education should run parallel to children's

education (Snodgrass et al., 2017). Consistent with the weaknesses found in

previous work, this study posed the following research questions:

1. What are the early

intervention practices that improve child development outcomes, summarized in

an early childhood developmental assessment manual (birth to age five)?

2. Can a website be

designed with developmental assessment tools and intervention exercises for

children?

3. Can a mobile

application (educational app) be drafted to facilitate access to a website with

illustrations of milestones of children's progress between 0 and 5 years of

age, and their follow-up?

4. Can an educational

app focused on families and professionals of children 0-5 years old be

evaluated and its effects measured?

2. Methodology

We used a mixed-methods

approach (evidence-based practice, action research, formative evaluation and

technology integration).

2.1. Participants

Non-probability sampling was

employed in which families and professionals were chosen by utility, as in the

study by Subiñas et al. (2022) which has served as an example approach. The

formative evaluation of the educational App was developed in La Laguna

(Tenerife). After ethical approval by the University, detailed information was

given orally and by telephone to families and professionals. The sample

consisted of 51 cases of children and 62 families and professionals who

authorized the experiment. The total number of participating

infants were as follows: 30 boys and 21 girls. The children were 1 year

old (14 cases), 2 years old (24), 3 years old (6), 4 years old (5), 5 years old

(2) and 8 years old (1).

The gender of family members

and professionals was predominantly female (82.3%, N=51) versus male (17.7%,

N=11). The predominant age of family members and professionals was 18-29 years

(58.1%, N=36), 30-39 years (17.7%, N=11), 40-49 years (16.1%, N=10) and over 50

years (8.1%, N=50). The size of members using the educational App was 47. Of

these, professionals used the educational app (61.7%), followed by family

members (36.2%). Of the 61 responses received, the highest academic degree

received was bachelor's (50%, N=31), doctorate (24.2%, N=15), bachelor's

(17.7%, N=11) or master's (8.1%, N=5).

2.2. Instruments

First, the UPDating University

Curricula on Early Intervention (UPDEIT) team developed an Early Care Manual[1]. From 0 to 5 years following the evidence-based practice method. It included

text and illustrations for the early detection of visual and hearing problems

and the assessment of motor development. It was translated into the four

languages (English, Greek, Macedonian and Spanish) of the countries

participating in the UPDEIT project. It was a teaching resource aimed at

educators and students in teacher training programs such as the Early Childhood

Developmental Screenings Guidebook (Louisiana Department of Education, 2023).

Second, it established an open source Internet Open Educational Resource (OER),

following an action research method and webinars[2] with members of the UPDEIT team. It was dedicated to child development

covering screening tools, intervention exercises and strategies adapted to

developmental delays in perception, gross motor, fine motor, personal-social

development, communication, play and social development in four languages

(English, Greek, Macedonian and Spanish) (Table 1).

Table 1

Open Educational Resource (OER)

|

GUESS WHICH HAND IT IS IN (PERCEPTION AREA) |

|

Take a small toy and

hide it in one of your palms. The first time, let the child see which palm

you will hide the toy in. Then ask him which hand the toy is in and let him guess.

The next time, don't show him which hand he is

putting the toy in and ask him again where it is and let him guess. The

activity is suitable to stimulate the child's curiosity in searching for

objects. |

|

OPEN - CLOSE (MOTOR

SKILLS, PERCEPTION, INDEPENDENCE) |

|

Opening and closing are

very interesting activities for children, whether it is a door, a window or a

drawer. They like to open them and see what is inside. Teach the child to

open and close different types of doors: sliding, regular.... Pay attention

to the child's hands and feet while doing the activity. |

|

PUTTING OBJECTS IN AND

TAKING OBJECTS OUT (MOTOR SKILLS, PERCEPTION, INDEPENDENCE) |

|

Prepare a transparent

box or jar with a wide opening through which the child can reach a small

ball. Show the child how to put the ball in the jar and then take it out.

Assist them in their attempts. |

|

PLAYING WITH PAPER

(PERCEPTION, FINE MOTOR) |

|

Use different types of paper

and show the child how it can be crumpled, twisted, pulled and used to make

origami. This activity stimulates the child's imagination and creativity. |

|

PILED CUPS |

|

Take several plastic

cups and show the child how to stack the cups inside each other, then help

the child stack them independently. |

|

BLOCK TOWER |

|

Start with three blocks,

showing the child how to build a block tower. Help as needed. At this age, it

may take some time for the child to master the skill. Allow the child to

knock over the tower if he/she wants to. |

|

MOVING LARGE OBJECTS |

|

Give the child a large,

soft pillow or toy and allow him/her to move with it. This is important for

maintaining balance and control when walking with reduced visibility of the

floor, encouraging spatial assessment. |

|

GETTING TO KNOW FAMILY

MEMBERS |

|

Take a photo album or

pictures from your phone and introduce each family member by name and the

child's relationship to them. Repeat and encourage the child to say his or

her name when you show him or her a picture of a specific person. If you do

this often, it will be easier for the child to recognize and then name the

faces he or she sees in the pictures. |

|

TICKLE TIME |

|

Sit with the child in

front of a mirror. Tickle the child's feet and the child will see in the

mirror where you are tickling them. Tickle other parts of his body as well,

naming the part that is tickling him at that moment. This is a fun way for

the child to learn body parts and, at the same time, develop self-awareness. |

|

FUN WITH GRAVITY |

|

Take a rubber ball and

drop it. When it bounces on the ground, catch it again. Drop the ball from

different heights and show the child what happens. Also, show him that the

ball is simply falling and he is not throwing it. You can also drop other

objects from your hand so the child can see that they do not bounce like the

ball. |

|

DANCE (MOTOR AREA -

BALANCE AND RHYTHM) |

|

Once the child begins to

balance, show him that music is fun and that we can move our bodies to the

beat. This activity introduces the child to dance. Watching you, the child

will begin to move his arms and body during the songs. You can also sing the songs and move your body along with the child. |

|

IMPORTANT CONVERSATION

(SPEECH AND COMMUNICATION AREA) |

|

When the child is in a

good mood and comes to you after finishing a game, start a conversation by asking

brief questions. Consider every sound uttered as a response. Initiate

frequent conversations on different topics: what was the game like, what were

you doing when the child arrived, what is daddy doing, what will he do next,

etc. Be enthusiastic in asking questions, even when the child cannot yet

answer. Instead of the child, you can always give the answer, introducing the

child to interaction and learning from a model. Even when the child attempts

to vocalize, accept it as an answer and confirm the attempt by giving the

full answer on his or her behalf. |

|

GETTING OUT OF BED

(MOTOR AREA) |

|

Place the child on a

soft surface such as a bed that is no higher than the child's neck. Next, lay

the child on his side on the edge of the bed, help him grasp the surface with

his hands, and then move him so that his legs dangle down. Holding his hands,

let the body move slowly downward. When he stands on the floor, praise him

enthusiastically for his effort. Repeat the same thing several times

throughout the day, holding his hand, until he is confident to lie down on

his own. |

|

HIDE AND SEEK

(PERCEPTUAL, PLAY, SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT) |

|

Play hide-and-seek by

hiding in easy places and calling out to the child. When they are close to

your hiding place, come out and yell “Boo!”, but be careful not to startle

the child. Repeat the game from time to time. After a few times, the child

will understand the concept and will be able to change their hiding place. |

|

MAINTAIN FOCUS (AREA OF

PERCEPTION, LOGIC, AND REASONING). |

|

While the child is

interested in playing with a favorite toy, take it, wrap it in several pieces

of paper, and put it in a laundry basket while you watch. Then ask him where

the toy is. You will have to help him find it at first, but eventually, he

will begin to find it on his own. This helps develop focus and persistence. |

|

GESTURE COMMUNICATION |

|

Communication is

incomplete without hand and body gestures. Tell stories or anecdotes with

full hand and body movements so that the child learns to express himself

through gestures and facial expressions, not just words. For example, when

you are excited and yell “Yay!”, hold up your hands. |

|

LEARNING ABOUT ANIMALS |

|

Show the child different

animals on your phone or cards (lion, monkey, horse, etc.) that are difficult

to see in everyday life. Start with the ones he/she already knows. Introduce

the sound and movement each animal makes. |

Third, we outlined an educational

app as an accessible and convenient way to monitor children's growth and

development contained in the OER that was used by family members and parents,

and that could be extended to caregivers and health professionals to identify

possible developmental delays and provide early interventions. This had

highlighted prominent mobile apps (CDC's Milestone Tracker (https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/actearly/milestones-app.html), BabySparks (https://babysparks.com/es/ ), Kinedu (https://app-es.kinedu.com) or Grow by WebMD (https://www.webmd.com/baby/default.htm). These apps include lists of developmental milestones by age, offer

personalized activities to support children's cognitive, motor, social and

emotional development, progress tracking, health and nutrition advice, language

development assessments for use by family members and parents.

The UPDEIT educational app

used the term “haptics” associated with touch (Pila et al., 2021), and was available on iOS and Android platforms that

ensured security, usability, versatility, and data protection for users.

Finally, the Questionnaire

Experience of Use (CEU) was a subjective test aimed at describing, classifying

or rating the satisfaction of parents and family members with the educational

app. The questionnaire had the format of a semantic differential of Osgood

(1964). It was composed of six dimensions (attractiveness, transparency,

efficiency, controllability, stimulation and novelty) and 26 pairs of

antonymous adjectives on a seven-point scale. It operated on paper and Google,

like other questionnaires (Lohmann et al., 2024).

To the knowledge of binary

adjectives that were at the extremes of agreement (+), i.e., 5, 6, and 7, and

disagreement (-), i.e., 1, 2, and 3 of a word, a value of 4 representing

partial knowledge of the evaluative item or item was added. These values of the

CEU scale were represented as shown in Table 2. In this way, greater evaluative

sensitivity was gained.

Adjetives

Adjetives

__ __ __

__ __ __ __

Unpleasant -3 -2 -1

0 +1 +2 +3 Pleasant

Each meaning is reflected in

the following table (Table 2)

Table 2

Meaning of the numeric system to interpret the scale

|

Numerical system |

Meaning |

|

+3 |

Very pleasant |

|

+2 |

Quite pleasant |

|

+1 |

Somewhat pleasant |

|

0 |

Neither pleasant nor

unpleasant |

|

-1 |

Somewhat unpleasant |

|

-2 |

Quite unpleasant |

|

-3 |

Very unpleasant |

2.3. Procedure

The effectiveness indicators were

determined by the successive revisions of the Early Intervention Manual. From 0

to 5 years through webinars.

Then, members of the

Macedonian (Saints Cyril and Methodius University of Skopje, and

Училница

Даскаловски/

Ucilnica Daskalovski) and Cypriot (Frederick University) teams of the UPDEIT

project designed a website

(https://mdl.frederick.ac.cy/UPDEITPlatform/Dashboard) that included

interactive and multimedia elements with other structural ones. The validation

of the website occurred after successive webinars with all the international

members of the project.

Subsequently, researchers from

the Cypriot team at Frederick University made the digital transformation by

designing an educational app for smartphones that allowed the management of the

developmental milestones of children from 0 to 5 years of age of the OER. The

validation of the design of the educational app was carried out by applying a

checklist that was completed in an international face-to-face meeting of the

UPDEIT team held at the University of La Laguna in 2023 (See https://updeit.eu//Main/News).

Finally, seven researchers

from the UPDEIT team from La Laguna, specializing in inclusive education

applied the educational app with 51 children and 62 adults (51 professionals

and 11 families -parent-) to understand the feasibility of its use. They evaluated

the treatment fidelity of the educational app, conceptualized as adherence, as

suggested by Collier-Meek et al. (2020: 335-336). The formative evaluation took

place between February and March 2023. Each researcher had one or more

professionals and family members with their children. Each educational app

evaluation session lasted approximately 15-25 minutes.

2.4. Data analysis

The evaluative analysis of the

educational app had not been guided by any previous research hypothesis or

theory, as had occurred in a study among educators and designers of this style

of technology (Kucirkova & Flewitt, 2020). As we indicated, each professional

and family member’s response to the CEU was scored on a seven-point graduated

ruler or Likert-type scale, with 1 and 7 being the extreme values for bipolar

adjectives, following Osgood's (1964) semantic differential technique.

The antonymic or binary adjectives

measured gradients in the six CEU dimensions: attractiveness

(unpleasant-unpleasant; bad-good; repellent-attractive, awkward-comfortable,

ugly-suggestive, unpleasant-sympathetic), transparency

(incomprehensible-comprehensible; intricate-simple; complicated-easy,

confusing-clear), efficiency (slow-fast, inefficient-efficient,

theoretical-pragmatic, anarchic-orderly), controllability

(unpredictable-predictable, obstructive-expeditious, insecure-unsure;

unconcerned-expectant), stimulation (insignificant-valuable, boring-exciting,

dull-interesting), and novelty (chimerical-creative, conventional-original,

familiar-novel, routine-innovative).

3. Results

The study employed a

combination of statistical tests to analyze data and understand the

relationship between variables, as well as to determine the reliability of the

results. The Fisher-Snedecor F-test was used to compare the variance of more

than two sets of data and to determine if there was a significant difference

between the means of the populations from which the samples were drawn. The

chi-square coefficient (χ²) was used to determine whether there was a significant relationship

between two or more categorical variables, and a reliability analysis was used

to assess the consistency and stability of a measure in different situations,

as other researchers had proceeded in their work (Posokhova et al., 2016).

In the present study, two CEU

reliability coefficients were applied: the Cronbach's Alpha coefficient for six

dimensions and N= 62 with a value of .943 and the Guttman discrimination

coefficient in the dimensions: attraction (.786), transparency (.948), efficiency

(.943), controllability (.913), stimulation (.921) and novelty (.946). In both

cases, the semantic differential had internal consistency

reliability and the ability to discriminate between people with high and low

scores on each dimension. Table 3 shows the means, standard deviations,

variance and mode of the dimensions.

Table 3

Means and standard deviations of the dimensions

|

Dimensions |

Means |

Standard deviations |

Skewness |

Kurtosis |

|

Attraction |

4.35 |

1.784 |

-.649. |

-1.113 |

|

Transparency |

5.40 |

1.336 |

-.744 |

-.021 |

|

Efficiency |

5.47 |

1.082 |

.006 |

-1.261 |

|

Controllability |

5.79 |

1.103 |

-.475 |

-.791 |

|

Stimulation |

5.95 |

1.220 |

-.856 |

-.316 |

|

Novelty |

5.50 |

1.211 |

-.372 |

-.558 |

The greatest dispersion around

the mean explained by the variance was in the attraction dimension, which was

also observed in the spread of the data around the mean value (standard

deviation). The mode indicated that 6 (quite pleasant) and 7 (very pleasant)

were the predominant or most representative values of the six dimensions.

Table 4 shows the chi-square statistics

for the dimensions and the p-value associated with each dimension. Since the

p-value was less than the α (.05) level of significance in four dimensions: attractiveness, controllability,

stimulation, and novelty, the null hypothesis was rejected, concluding that

there was a significant relationship between these dimensions.

Table 4

Contingency table of chi-square test of the dimensions

|

|

Attraction |

Transparency |

Efficiency |

Controllability |

Stimulation |

Novelty |

|

Chi-Squared |

36.226 |

29.613 |

21.548 |

37.613 |

97.032 |

29.355 |

|

Sig. |

p<.001 |

p<.057 |

p<.063 |

p<.001 |

p<.001 |

p<.001 |

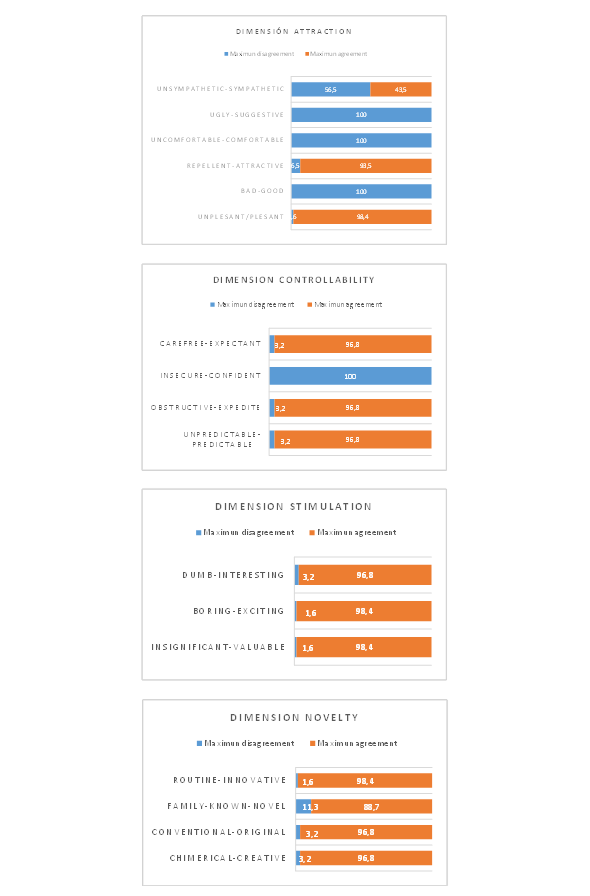

Figure 1 shows the graphical representation of the values

obtained for the dimensions that were found to be significant.

Figure 1

Representation of the values of the elements in the dimensions attraction,

controllability, stimulation and novelty of the semantic differential

Of the six attractiveness

items, three attitudes had a rating of “maximum disagreement” (ugly,

uncomfortable and bad), indicating that the educational app was presented as

suggestive, comfortable and good. The unsympathetic-sympathetic pair, however,

shows a mean rating between unsympathetic and sympathetic.

In addition, subjects had a

totally positive perception (interesting, exciting and valuable) on three

elements of stimulation and on four elements of novelty (innovative, novel,

original and creative). Likewise, three items (expectancy, expediency and predictability)

were totally positive and one totally negative in controllability, which

represented the perception of “maximum disagreement” and, therefore, there was

no insecurity in the educational app.

Strengths indicated that users

found the educational app engaging and motivating (stimulation). Also, that it offered something different and fresh compared

to other options on the market (novelty), and they knew what to expect from the

educational app, that it worked efficiently, safely, and that it was easy to

understand and use. The educational app is rated in the attractiveness

dimension as suggestive, comfortable, appealing, good and pleasant.

As a somewhat weaker point, it

seems that the educational app is rated somewhere between nice/unfriendly and a

small percentage (11.3%) find it not very novel.

There were no significant

differences between families and professionals, according to gender and

academic qualifications of the users.

However, there were

significant differences in terms of subjects' age in three dimensions:

attraction (F=5.126, 3gl, p<.003) with the following values: 18-29 (x̄=5.63,

σ=. 499), 30-39 (x̄=4.88, σ=.817), 40-49 (x̄=5.22, σ=.676) and highlighting the significant difference between the 18-29 and

30-39 group (F=4.84, 45gl, p<.001) with higher mean

in the case of 18-29.

In the efficiency dimension

(F=2.966, 3gl, p<.039), the following values are presented by age: 18-29 (x̄=5.61,

σ=1.004), 30-39 (x̄=4.66, σ=861), 40-49 (x̄=5.60, σ=1.113), and >50 (x̄=5.00, σ=968). Furthermore, it stands out that the 18-29 age group (x̄=5.61,

σ=1.004) manifests a significant difference with the 30-39 group (x̄=4.66,

σ=861) (F=.434, 45gl, p<.007).

In the stimulation dimension

(F=4.836, 3gl, p<.005) significant differences were obtained by age: 18-29

(x̄=6.24, σ=.950), 30-39 (x̄=4.84, σ=1.393), 40-49 (x̄=5.38, σ=1.506), and >50 (x̄=5.90, σ=1.069). The largest significant difference was between age group 18-29

(x̄=6.24, σ=.950) and 30-39 (x̄=4.84, σ=1.393), (F=2.086, 45gl, p<.001).

Likewise, significant

differences were found concerning the academic degree of the sample in the

controllability dimension (F=3.950, gl3, p<.012): Master's degree (x̄=4.40,

σ=1.506), PhD (x̄=5.85, σ=.944), Bachelor's degree (x̄=6.00, σ=.944) and Bachelor's degree (x̄=5.43, σ=1.090). The largest significant difference was between those with

Bachelor's education (x̄=6.00, σ=.944) and Bachelor's (x̄=5.43, σ=1.090) with a significant difference (F=12.298, 3gl, p<.012).

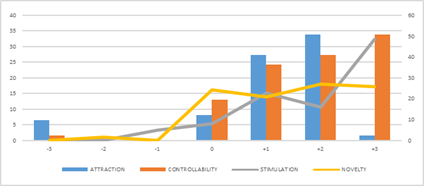

Figure 2 shows graphically

that the maximum pole (+3 “very pleasant”) in the pleasant consideration of the

app is the stimulation dimension followed by controllability and novelty. It is

followed by the consideration of “quite pleasant” (+2) where attraction

occupies a relevant role followed equally by controllability and novelty.

“Somewhat pleasant” (+1) is rated by those who emphasize attraction in the app,

then controllability, followed by stimulation and finally novelty.

Note that average scores

somewhat outstanding can only be mentioned novelty and the values of the

negative poles in the proposed adjectives is very minority..

Figure 2

Gradation in the evaluation of the adjectives (-3 to +3) organized in the

four dimensions that obtained significant values

However, there were

significant differences about the age of the subjects

in three dimensions: attraction (F=5.126, 3gl, p<.003), efficiency (F=2.966,

3gl, p<.039) and stimulation (F=4.836, 3gl, p<.005). Likewise,

significant differences were found to the academic degree of the sample in the

controllability dimension (F=3.950, gl3, p<.012).

Figure 3 shows graphically

that the stimulation, controllability and novelty dimensions are located at the

maximum pole (+3 “very pleasant”) of the educational app. It is followed by the

gradient “quite pleasant” (+2) where attraction occupies a relevant role

followed equally by the controllability and novelty dimensions. Subjects rated

“somewhat pleasant” (+1) the educational app dimensions attraction, followed by

controllability, stimulation and novelty.

Note that the novelty

dimension obtains the mean scores somewhat prominent in the pleasantness

scalar gradients, while the adjectives located in the unpleasantness scalar

values are very little perceptible.

Figure 3

Gradation in the evaluation of the adjectives (-3 to +3) organized in the

four dimensions that obtain significant values

4. Discussion

The evaluative objective of

the educational app was to ascertain the perceptions of family members and

professionals targeting children ages 0-5 years focused on six dimensions

(attractiveness, transparency, efficiency, etc.) measured through CEU.

The findings of this research

problem indicated that the age of family members and professionals made a

powerful difference in the attractiveness, efficiency and stimulation

dimensions of CEU, while academic degree only did so in the controllability

dimension.

Attraction was not a

unidimensional concept, because it described the intensity of a sensory

reaction, alluded to the moral and ethical evaluation of something, focused on

the physical and emotional sensation experienced by the subjects, on the

aesthetic perception of the educational app and on the possibility of

connecting with someone through it. In this dimension, there was a significant

difference between the 18-29 and 30-39 groups, with a higher mean

in the case of the 18-29 group, reflecting the fact that the younger the age,

the more attractive the educational app was considered to be.

Efficiency was the ability to

achieve a given objective with the minimum possible resources and time. It also

indicated a balance between theory and practice, and

was related to the organization and structure of a process. In the efficiency

dimension, the 18-29 age group shows a significant difference with the 30-39

group. The younger group emphasizes the efficiency of the educational app.

Stimulation, caused by

relevance, intensity and motivation, was the ability of an incitement (in this

case the educational app) to capture attention, arouse interest and generate a

response in a sample subject. In this dimension, significant differences were obtained by age, with the greatest significant difference

being with the 18-29 age group. Again, the younger group found the educational

app stimulating.

There were significant

differences between subjects with different academic degrees in the

controllability dimension. Thus, graduates perceived greater controllability in

the educational app than subjects with a bachelor's degree.

The educational app offered

something different and fresh with an efficient, safe and easy to understand

and use operation. The attraction dimension showed that it was suggestive,

comfortable, appealing, good and pleasant. On the other hand, it was rated

somewhere between nice/antipathetic and a small percentage of subjects found it

not very novel.

The evaluation of the

educational app provides contributions regarding the educational technology

contained in the OER manual and, specifically, the future design of digital

personalization of smartphones for use by parents, caregivers, educators, and

health professionals. First, it focuses on convergences of the educational app.

What views were shared by family members and professionals? Considering the

sample by gender, they responded with the same perceptions in all dimensions.

Classified by academic level, their perceptions were the same in all

dimensions, except controllability, and ordered by age, they had analogous

perceptions in transparency, controllability and novelty.

The main difference between

subjects occurred for reasons of age and academic level. Understanding these

convergences and divergences between family members and professionals, as

Kucirkova & Flewitt (2020, p. 146) did, is crucial for the development of

successful strategies for the implementation of the educational app in initial

teacher training and in early childhood education teacher development. This had

been suggested by researchers in other contexts (Dunst, 2019),

and so could be implemented in cultural and educational contexts

analogous to Tenerife.

4.1. Limitations and

implications

The results should be

interpreted with some caution for several reasons. First, family members and

professionals evaluated an educational app with a semantic differential that

they were unfamiliar with and may have been reluctant because it was the first

time they met with a researcher, as Goh et al. (2015, p. 794) mentioned in

their study; second, the dimensions of the semantic differential included

elements that should have been rationally and empirically justified; third, the

educational app was a technological tool based on OER evidence that encompassed

areas of child development, (communication, motor, social-emotional

development, etc. ); however, the semantic differential did not identify

possible delays in child development in key areas that would allow for early

and effective intervention, as was the case with the ASQ (Ages & Stages

Questionnaires, third edition) by Squires & Bricker (2009). And third, the

accessibility of the app for parents and trainers was not ideal, because

telepractice involves the use of technologies such as video calls, interactive

platforms or applications to provide educational, therapeutic or training

services at a distance.

Technological implications

applied to early childhood care: Design and usability. The educational app

needs an urgent renovation in its visual design and

usability. Priority should be given to the creation of an attractive, intuitive

and user-friendly interface. Emotional connection. An emotional connection must

be created with the users. This can be achieved through a friendly language, an

attractive interface and a focus on users' needs and preferences. Security.

Addressing the perception of insecurity is critical. Robust security measures

should be implemented and clearly communicate to users

how their data is protected. Leverage strengths. Capitalize on the positive

perception of stimulation and novelty. You can continue to innovate and offer

interesting and valuable content to keep users motivated and engaged.

5. Conclusions

The results obtained have led to the following

conclusions linked to the initial questions:

First, creation

of the REA manual that summarizes early intervention practices that improve

child development outcomes.

Second, OER has incorporated

child development assessment tools and intervention exercises for children.

Third, an educational app has

facilitated access to OER.

Finally, family and

professional perceptions of the educational app on child development between 0

and 5 years of age have been tested.

Author

contributions

Conceptualisation, V.A.-L.M.; Data curation,

V.A.-L.M., A.R.-O.M.; Formal analysis, V.A.-L.M., A.R.-O.M.; Investigation,

V.A.-L.M., A.R.-O.M.; Methodology, A.R.-O.M.;

Project administration, A.R.-O.M.; Supervision, V.A.-L.M., A.R.-O.M.;

Validation, V.A.-L.M., A.R.-O.M.; Writing—original draft, V.A.-L.M., A.R.-O.M.;

Writing—review and editing, V.A.-L.M., A.R.-O.M.

Funding

European

Union funded project KA2: UPDating University Curricula on Early Intervention

(UPDEIT). Erasmus+ European Union competitive project nº

2021-1-MKO-1-KA2-2-0-HED-0000229812 2022-2024

Data Availability Statement

The data set used in this

study is available at reasonable request to the corresponding author

Ethics approval

Not aplicable

Consent for publication

The author has consented to the

publication of the results obtained by means of the corresponding consent forms

Conflicts of interest

The author declares that they

have no conflict of interest

Rights and permissions

Open Access. This article is licensed under

a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction

in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original

author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and

indicate if changes were made.

References

Bonilla, M. y Aguaded, I.

(2018) La escuela en la era digital: smartphones, apps

y programación en educación primaria y su repercusión en la competencia

mediática del alumnado. Pixel Bit. Revista

de Medios y Educación, 53, 151-163. http://dx.doi.org/10.12795/pixelbit.2018.i53.10

Collier-Meek, M. A., Sanetti, L. M. H., Gould, K.,

& Pereira, B. (2020). Una comparación

exploratoria de tres métodos de evaluación de la fidelidad del tratamiento:

muestreo de tiempo, registro de eventos y lista de verificación posterior a la

observación. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 31 (3),

334–359. https://doi.org/10.1080/10474412.2020.1777874.

Departamento de Educación de Luisiana (2023). Guía de evaluación del desarrollo infantil

temprano. ERIC: ED647582.

Dunst, C.J., Bruder, M.B., Maude, S.P., Schnurr, M.,

Van Polen, A., Clark, G.F., Winslow, A., & Gethmann, D. (2019).

Professional Development Practices and Practitioner Use of Recommended Early

Childhood Intervention Practices. Journal of Teacher Education and

Educators, 8(3), 2019, 229-246. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1240077.pdf

Fidan, N. K., & Olur, B. (2023). Examining the relationship between

parents’ digital parenting self-efficacy and digital parenting attitudes. Education

and Information Technologies, 28, 15189–15204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-023-11841-2.

Goh, W., & Bay, S., & Chen, V. (2015). Young

school children's use of digital devices and parental rules. Telematics and

Informatics, 32. 787-795. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2015.04.002.

Hudson, M.E. (2019). Using iPad-delivered Instruction

and Self-Monitoring to Improve the Early Literacy Skills of Middle School

Nonreaders with Developmental Disabilities. International Journal of Special

Education, 34(1), 182-196. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1237171.pdf

Kucirkova, N., & Flewitt, R. (2020). The

future-gazing potential of digital personalization in young children’s reading:

Views from education professionals and app designers. Early Child

Development and Care, 190 (2), 135-149. https://

doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2018.1458718

Lim, S. (2017). Mobile Documentation with Smartphone and

Cloud in an Emergent Curriculum. Computers in the Schools, 34(4),

304-317, https://doi.org/10.1080/07380569.2017.1387469.

Lohmann, M.J., Riggleman, S., & Higgins, J. P.

(2024). Uso de un dispositivo móvil para la

recopilación de datos sobre el comportamiento en el aula en la primera

infancia. Early Childhood Educ J, 52, 427-434. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-023-01443-5.

McClelland, M.M., Tominey, S.L., Schmitt, S.A., &

Duncan, R. (2017). Intervenciones

SEL en la primera infancia. El futuro de los niños, 27(1), 33-47.

Merdin, E., & Şahinb, V. (2023). Young

Children’s Electronic Media Use and Parental Rules and Regulations. Journal

of Learning and Teaching in Digital Age, 8(2), 187-196.

Mertala, P. (2019). Young Children’s Conceptions of

Computers, Code, and the Internet. International Journal of

Child-Computer Interaction, 19, 56–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcci.2018.11.003.

Odom, S.L., & Wolery, M. (2003). Una teoría unificada de la práctica en la

intervención temprana/educación especial en la primera infancia: prácticas

basadas en la evidencia. The Journal of Special Education, 37 (3),

164–173. https://doi.org/10.1177/00224669030370030601.

Osgood, C. E. (1964). Semantic Differential Technique

in the Comparative Study of Cultures. American Anthropologist, 66,

171-200.

Parnell, W., & Bartlett, J. (2012). iDocument: How

smartphones and tablets are changing documentation in preschool and primary

classrooms. Young Children, 67(3), 50-59

Pila, S., Lauricella, A. R., Piper, A. M., &

Wartella, E. (2021). El

poder de las actitudes de los padres: análisis de las actitudes de los padres

hacia la tecnología tradicional y emergente. Human Behavior and

Emerging Technologies, 3(4), 540-551. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbe2.279.

Posokhova, S., Konovalova, N., Sorokin, V., Demyanov,

Y., Kolosova, T., & Didenko, E. (2016). System of attitudes in parents of

young people having sensory disorders. International Journal of

Environmental & Science Education, 11(16), 8956-8967. ERIC number:

EJ1118954.

Squires, J., & Bricker, D. (2009). Ages &

Stages Questionnaires, Third Edition (ASQ-3). Baltimore, MD: Brookes

Publishing Co.

Snodgrass, M. R., Chung, M. Y., Biller, M. F., Appel,

K. E., Meadan, H., & Halle, J. W. (2017). Telepractice in Speech–Language

Therapy: The Use of Online Technologies for Parent Training and Coaching. Communication

Disorders Quarterly, 38(4), 242-254. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525740116680424.

Sørenssen, I. K., & Bergschöld, J. M. (2021).

Domesticated Smartphones in Early Childhood Education and Care settings.

Blurring the lines between pedagogical and administrative use. International

Journal of Early Years Education, 31(4), 874–887. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760.2021.1893157.

Subiñas Medina, P.,

García-Grau, P., Gutiérrez-Ortega, M., & León-Estrada, I. (2022). Family-centered

practices in early intervention: family confidence, competence, and quality of

life. Psychology, Society & Education, 14(2), 39–47. https://doi.org/10.21071/psye.v14i2.14296.

Vidal-Hall, C., Flewitt, R., & Wyse, D. (2020).

Early childhood practitioner beliefs about digital media: integrating

technology into a child-centred classroom environment. European Early

Childhood Education Research Journal, 28(2), 167-181. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2020.1735727.

Wallace, I. F. (2018). Universal Screening of Young Children

for Developmental Disorders: Unpacking the Controversies. RTI Press Publication

No. OP-0048-1802. Research Triangle Park, NC: RTI Press. https://doi.org/10.3768/rtipress.2018.op.0048.1802.

Wert, J. (2023). Partnering With Children

Through Visual Documentation. Childhood Education, 99(2),

60–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/00094056.2023.2185046.

Williams, C.

(2021). Learning and Literacy Through Image-Based Story. Childhood

Education, 97(3), 32–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/00094056.2021.1930911.

Zomer, N.R., & Kay, R.H. (2016). Technology Use in

Early Childhood Education. Journal of Educational Informatics, 1,

1-25, https://journalofeducationalinformatics.ca/index.php/JEI/article/view/45.